Our post today comes from the blog PRESBYTERIANS OF THE PAST. This is a blog written by our good friend Barry Waugh. His blog posts are typically fuller treatments of a subject than we can afford here, but today I will be presenting one of his blog posts in its entirety. The subject of today’s post is the Rev. Alexander Waugh (no relation to our author!):

Alexander Waugh, 1754-1827

by Barry Waugh.

Alexander was the last child born to Thomas and Margaret (Johnstone) Waugh in their modest but comfortable home located about thirty-five miles southeast of Edinburgh in East Gordon, Berwickshire. The wee one entered a family, August 16, 1754, where home, church, and Scotland were important. Thomas was a farmer, a good father, and a third-generation Covenanter, but he knew himself well enough to discern that he was not an elder and declined the office when asked. Alexander’s maternal grandparents were Alexander and Elizabeth (Waugh) Johnstone which may indicate his father and mother were kin based on grandmother Elizabeth’s maiden name.

Scotland had a good educational system because its parish schools were developed from the plan provided in John Knox’s First Book of Discipline, 1560. Alexander graduated from tutoring at his mother’s knee at an undetermined age to attend school with the local children. The daily curriculum included Bible reading and reciting the Westminster Shorter Catechism. At the age of twelve he transferred to the grammar school in not-too-distant Earlston to study Latin and Greek with Master John Mill. During this time, he contracted smallpox, common in the day, but fortunately it was a mild case. When Alexander was sixteen, he left his Covenanters heritage to unite with the Secession Church, Burgher, in Stitchell during the ministry of George Coventry. The Secession Church was at the time divided in two as Burghers and Anti-Burgers.

In 1770, Waugh entered Edinburgh University. His studies in Latin and Greek continued but added to his language acquisition list was Hebrew. He enjoyed Latin, cared less for Greek, and found Hebrew to be on the unpleasant side. Professor of Moral Philosophy Adam Ferguson was his favorite instructor, but unbeknownst to Alexander his instructor was lacing elegant words with too high a view of reason and human nature. Ferguson had abandoned the ministry several years earlier and recently published his Enlightenment influenced Institutes of Moral Philosophy.

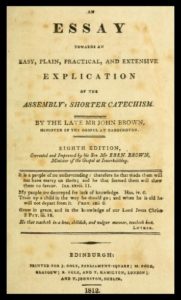

After completing Edinburgh, Waugh was examined by presbytery and admitted to ministerial training in the Burgher Secession Academy mastered by John Brown of Haddington. Brown was a self-taught minister who had grown up in abject poverty but became influential not only for Christians of his day but also for generations to come. His book, Self-Interpreting Bible, 1778, was a well-received title among several beneficial books published by him. It was a wonderful opportunity for Alexander, but things did not start well. According to a fellow student his first discourse before class was presentation of a philosophical essay “at which the professor and students were extremely grieved” and Brown said, “I hope I shall never hear such a discourse again in this place.” It was not the way to start off studies with Pastor Brown. Professor Ferguson’s philosophical perspective and didactic panache had unfortunately provided Alexander with the wrong presuppositional base, so Brown undid Waugh’s Edinburgh education for three years and continued the process by sending him to the University of Aberdeen for a year. Marischal College at Aberdeen was the antidote for Edinburgh. Faculty members that persuaded him greatly were James Beattie and George Campbell who both wrote against David Hume. Campbell had written Essay on Miracles and Beattie published An Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth, 1770. Waugh found both professors knowledgeable and informative, but Campbell, the divinity professor, was more congenial to Alexander’s thinking. It was really an important time in the history of philosophy because the rise of reason had descended into skepticism which was met handily by Thomas Reid and his commonsense compadres. Scottish Common Sense Realism was philosophy, not theology, but its epistemology was friendlier to Christian presuppositions than Hume’s empiricist skepticism. Waugh was granted the Master of Arts, April 1, 1778. Thanks to John Brown’s instruction, Alexander built his foundation on the theological rock of Scripture and the philosophically acceptable epistemology of Scottish Realism. Aberdeen trumped Edinburgh. The history of Christianity has repeatedly shown the devastating results of faculties that embraced aberrant views which were then passed on to ministers that propounded them from pulpits and led the following generations astray.

It is not clear what Waugh was doing between graduation and examination by the Presbytery of Edinburgh when it met at Duns, June 28, 1779, but he may have returned for further instruction from Brown. The meeting was presided over by his pastor from Stitchell, George Coventry. He passed the examination trials to become a probationer and was appointed to supply the Secession Church on Wells Street in London. The Wells Street congregation needed his ministry because the former pastor, Archibald Hall, had passed away. After a short time, he was invited to become pastor but instead he returned to Scotland and supplied pulpits until accepting a call from a poor country church in Newtown. A friend of his from Edinburgh days, George Graham, writing from his mission work in St. Croix discouraged him from accepting the call because he believed a city church was better suited for Waugh. Not only Graham but John Brown provided advice, however Brown took a different perspective. It seems that the new minister thought more highly of himself than he ought.

I know the vanity of your heart, that you will feel mortified that your congregation is very small in comparison of those of your brethren around you; but assure yourself, on the word of an old man, that when you come to give an account of them to the Lord Christ at his judgment seat, you will think you have had enough.

Alexander was ordained August 30, 1780 by presbytery then led worship September 3 in the Newtown Church. John Brown had proved persuasive as the Holy Spirit illumined Alexander’s heart. It was really a good situation for Rev. Waugh because he provided the small congregation with a pastor, and the limited salary provided by the church was not so great a problem for him because his father’s house was just thirteen miles away.

Waugh settled into work at Newtown, but the Wells Street Church in London continued to pursue him. After two attempts to call him in 1781, Wells Street accomplished its purpose in March 1782. The Presbytery of Edinburgh agreed with the move and appointed him to the London church to commence ministry the third Sabbath of June. His first sermon was from Psalm 45:2, “Thou art fairer than the children of men: grace is poured into thy lips: therefore, God hath blessed thee for ever.” He had refused a call when he supplied Wells Street as a probationer because he wanted to return to Scotland, but the persistence of the congregation overcame his national yen and his sense of God’s call led to settlement in London.

Two important personal events occurred within a few years of his installation at Wells Street. Alexander’s father died in 1783 and he married. The young lady was Mary Neill. Following pronouncement of the bans in the Church of England parishes of their residences, Alexander and Mary were united in marriage by Rev. John Riddoch of the Secession Church in Coldstream, Scotland, August 10, 1786. Their first child was born almost nine months to the day later and was named Thomas for his grandfather. It was a good beginning for the Waughs.

In addition to pulpit ministry Waugh catechized the children of his church the first Tuesday of every month after which the session met for an hour and then prayer meeting was held. How a session could accomplish its work in an hour a month must remain a mystery. During the winter, classes for the single men were held every Tuesday in order to study the Westminster Confession, discuss theological subjects, and consider recommendations from the pastor regarding books. There was a disproportionately large number of young men because many were moving from the country and other cities to London to find work in the growing number of factories created by the Industrial Revolution. The unmarried ladies’ event was not scheduled on Tuesday but instead on Monday so Waugh could meet with them once a month for tea and conversation. One might wonder how Mrs. Waugh played into these gender-separate events as a matchmaker. Likely not much because as the Waugh’s years of marriage passed, she became very busy with eleven children.

Key events during Alexander Waugh’s ministry were both within his connectional church and what would today be called interdenominational or parachurch ministries. The greatest event for his church was the reunion of the Burghers and Anti-Burghers of the Secession Church in 1820. After an amicable meeting and reunion, Waugh led the remainder of the session in prayer and devotional exercises. His interest in missions led to membership on the organizing committee that founded the London Missionary Society, 1795. He was the chairman of the candidate examination committee for the Society for twenty-eight years and travelled in its behalf throughout England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales as well as in France. During one trip he visited forty-six locations in two months and preached numerous times. Other interests included membership in the Corresponding Board of the Society for Propagating Christianity in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, the Scottish Hospital Society for thirty-seven years, and he was a member of the Irish Evangelical and Religious Tract Societies. He was not often published but after participation in the organizing committee for London’s Evangelical Magazine, 1793, he contributed some articles and all the memorials for deceased Scottish ministers. Alexander was honored with the Doctor of Divinity by Marischal College, 1815.

A key event in the ministry of Dr. Waugh had nothing to do with church, state, family, or foes, but was instead physical. In May 1823 the sixty-eight-year-old minister was leading a dedication service for construction of an orphanage at Clapton. The corner stone was being set and a scaffold was built for his use. Something in the scaffold failed and it collapsed. Pastor Waugh fell and severely injured his ankle. It incapacitated him for some time and he never fully recovered suffering limited mobility for the remainder of his life.

Alexander had been at Wells Street for forty-one years and the lengthy tenure, combined with possibly too much work outside his congregation, and his troublesome ankle may have contributed to restlessness among some members regarding his ministry. The session recognizing the infirmity of Pastor Waugh, the attitude of the flock, and the need to prepare for the future, sent him a letter in May 1827 asking him if they could seek student supplies for the pulpit. He would still be allowed to preach on occasion. He acquiesced but expressed concern about the financial cost to the church. The decision was a good one because the church was prepared when Alexander Waugh passed away December 14. His funeral was conducted by Revs. Roland Hill and Edward Irving in preparation for the procession of forty-two mourning coaches and thirteen private carriages to accompany his remains to Bunhill Fields for interment next to his son Alexander amidst generations of dissenters from the Church of England. The next Sabbath a memorial sermon was given in Wells Street by Rev. William Broadfoot on Job 5:26. Waugh’s lengthy memorial inscription on his grave includes the text of Job 5:26.

Mary survived Alexander. They had four sons enter the ministry, but one, Alexander, Jr., died at the age of twenty-nine shortly after he married and became a pastor. From Alexander’s near dozen children there were born twenty-six grandchildren to continue as seed of the Covenant and to remember their faithful grandpa.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The picture of Dunnottar Castle Cliffs, Aberdeen, is by Collie581 on Pixabay.

The terminology used to describe the Secession Church was for me confusing and varied from writer to writer. David C. Lachman’s articles “Associate Presbytery,” “Associate Presbyterian Churches,” along with the brief entry “Secession Church,” in which six ecclesiastical entities are listed, and help from K. R. Ross’s article, “Secessions,” combine to provide a sense of the complexity; see, Dictionary of Scottish Church History and Theology, IVP, 1993; my terminology is intended to keep it simple even though it is not as complete as it could be. The standard work on the Secession Church is from M’Kerrow’s History of the Secession Church, 2 vols., 1839.

See, David Laing, The Works of John Knox, vol. 2, 209f, concerning parochial schools.

Marriages of Dissenters, House of Commons, Debate 25 Fed. 1834, vol. 21, columns 776-89, provides debate showing the control the Church of England had over dissenting groups such as the Secession Church. The debate included discussion of whether marriage should be considered a civil or church function, which had been discussed more than 150 years prior by the Westminster Assembly. For more on bans and marriages in England see this site’s author’s post, “The Royal Wedding,” on Reformation 21.

The primary source for this post is A Memoir of the Reverend Alexander Waugh, D.D. with Selections from His Epistolary Correspondence, Pulpit Recollections, &c, by James Hay and Henry Belfrage, 2nd edition, London: Printed for Hamilton, Adams, and Co., 1831; the two portions in quotation marks about Waugh’s experience with Brown are from this book.

Sermons, Expositions, and Addresses at the Holy Communion, by the Late Rev. Alexander Waugh, A.M., Minister of the Scots Church in Miles Lane, London, 1825, includes material that is Alexander’s son’s work and not Alexander the father; it has a brief memoir of the young man’s life; no one is noted as the editor, but it is likely his father.

J. Ligon Duncan’s MA thesis at Covenant Seminary, “Common Sense and American Presbyterianism an Evaluation of the Impact of Scottish Realism on Princeton, ” 1987, provides a nice summary of Common Sense Realism in Scotland and then considers its influence at Princeton Seminary.

The quote by Brown is from Memoir and Select Remains of The Rev. John Brown, Minister of the Gospel, Haddington, edited by Rev. William Brown, M.D., Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, [1856?].

Broadfoot’s sermon was published in the pamphlet, The Christian Ripe for Eternity: A Sermon Preached in Wells Street Chapel, December 23, 1827, Occasioned by the Death of the Rev. Alexander Waugh, D.D., by the Rev. W. Broadfoot. To which is added the Address at the Grave, by the Rev. Robert Winter, D.D., [1828].