This Day in Presbyterian History is hosted by the PCA Historical Center, but we have tried to be somewhat ecumenical with this blog, looking at people and events in different denominations as opportunity permits. One denomination that I don’t remember having touched on is the United Presbyterian Church of North America (UPCNA). Officially formed in 1858, one historian noted that this denomination was “the result of several unions;” that “its antecedents are more numerous and fragmentary than those of most churches.” But to keep it simple, the UPCNA was formed by the merger of the Associate Presbyterian Church and the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church. Numerically they were strongest in Pennsylvania, Ohio and throughout the midwestern states.

This Day in Presbyterian History is hosted by the PCA Historical Center, but we have tried to be somewhat ecumenical with this blog, looking at people and events in different denominations as opportunity permits. One denomination that I don’t remember having touched on is the United Presbyterian Church of North America (UPCNA). Officially formed in 1858, one historian noted that this denomination was “the result of several unions;” that “its antecedents are more numerous and fragmentary than those of most churches.” But to keep it simple, the UPCNA was formed by the merger of the Associate Presbyterian Church and the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church. Numerically they were strongest in Pennsylvania, Ohio and throughout the midwestern states.

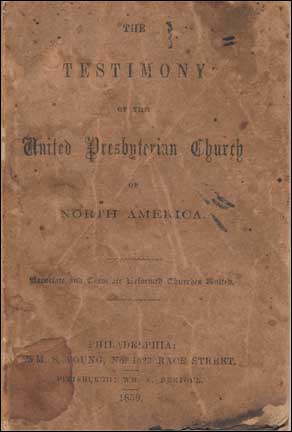

At its formation, the UPCNA issued a Testimony [pictured at right], which was a doctrinal statement consisting of eighteen articles, designed to set out the character and nature of the denomination. Notable among these articles was Article 14, which states,

We declare, That slaveholding human beings is involuntary bondage, and considering and treating them as property, and subject to be bought and sold—is a violation of the law of God, and contrary both to the letter and spirit of Christianity.

The “argument and illustration” supporting this Article continues for several pages and is too lengthy to reproduce here, but the conclusion was that no slaveholder could be a member in good standing in the UPCNA. In this conviction, the UPCNA followed the Reformed Presbyterians who took that same stand in 1802. And both these denominations lived out their principles in various practical ways.

So it was that in 1889 the UPCNA’s General Assembly adopted a motion to establish a ministry in Henderson, North Carolina, designed to serve primarily as a secondary school for blacks living in the Henderson area. A year later, in 1890, The denomination’s Board of Freedmen’s Missions had purchased thirteen acres of land just outside the Henderson city limits and in what must have been a very busy year, a school building and teacher’s cottage at the church’s Bluestone Mission in Virginia were broken down and then rebuilt on the Henderson Institute property. The official opening of the Institute took place on this day, September 1, 1891, with the Rev. J. M. Fulton serving as principal. He had formerly been the pastor of the Fourth Church, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, but was forced to relocate to a warmer climate for his health. Despite the cultural obstacles that might be expected in that time and place, the school was judged a success from the start. The initial enrollment of 556 students soon prompted a call for more teachers

So it was that in 1889 the UPCNA’s General Assembly adopted a motion to establish a ministry in Henderson, North Carolina, designed to serve primarily as a secondary school for blacks living in the Henderson area. A year later, in 1890, The denomination’s Board of Freedmen’s Missions had purchased thirteen acres of land just outside the Henderson city limits and in what must have been a very busy year, a school building and teacher’s cottage at the church’s Bluestone Mission in Virginia were broken down and then rebuilt on the Henderson Institute property. The official opening of the Institute took place on this day, September 1, 1891, with the Rev. J. M. Fulton serving as principal. He had formerly been the pastor of the Fourth Church, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, but was forced to relocate to a warmer climate for his health. Despite the cultural obstacles that might be expected in that time and place, the school was judged a success from the start. The initial enrollment of 556 students soon prompted a call for more teachers

and more buildings. During the two years that Rev. Fulton was there, over seven hundred students were enrolled in the day school and another two hundred students enrolled in the night school.

Of his time there at the Institute, in 1893 Rev. Fulton wrote bluntly, but with a measured optimism grounded in the Gospel, that:

The whole race is fenced in by the deep conviction of the whites, that the Negro was appointed by the Lord to do only menial [labor], and beyond that he cannot go. This is not prejudice on the part of the white people, but it is a religious conviction. The southern people will never do anything to change this condition. When we attempt to help the colored man we are told it is no use. … The only hope for the colored race is in the church—the benevolent people. The nation helped to crush the colored man and the Indian. The one she forsakes, the other she helps. Why this difference? Since God has put this work upon the Church let us arise to a realization of the needs of the people and strive to fit them for citizens of earth and heaven.

The Rev. C. L. McCracken followed Fulton and seemed to follow his conclusions as well, striving the connect the Henderson Institute more closely with the Church. Then in 1900, the Rev. J.L. Cook was the first African American to be appointed as principal of Henderson. He died after having served the school for three years, and was succeeded by the Rev. John Cotton, whose tenure lasted thirty-one years. The school finally closed in 1970.

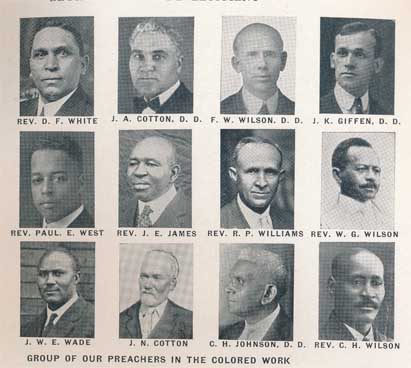

Lastly, in a short history of the UPCNA written by W.E. McCulloch (published in 1925), in a section on the Church’s work among blacks, there is this set of photos which includes two men named Cotton. One or the other of them may be the above mentioned principal of the Henderson Institute. The information at hand does not allow me to say which.

Words to Live By:

If the first chapters of the book of Genesis weren’t enough to demonstrate that all of humanity is related, then the remarkable event related in Acts 2 should have driven the point home that the divisions among the peoples of the world are now overcome by the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ. Parthians and Medes, Elamites, Judeans and Asians, Libyans, Cretes and Arabians, all that believed were together.

[Note: The Henderson Institute of Henderson, North Carolina is not to be confused with the Henry Henderson Institute, a school in Blantyre, Malawi, founded in 1909, and named in honor of Henry Henderson, a lay missionary from the Church of Scotland who founded the Blantyre Mission.]

No comments

Comments feed for this article