Rebuilding the Walls of Zion.

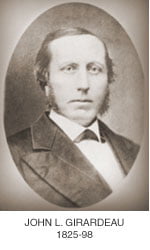

Our post today comes from the pen of guest author Dr. Nick Willborn, an excerpt from a longer article. Here Dr. Willborn tells of the return of the Rev. Dr. John L. Girardeau in 1865, to serve as pastor of the Zion Presbyterian Church in Charleston, South Carollina.

According to a longtime friend of the Rev. John L. Girardeau, it was about this time that “[Girardeau] began to receive overtures from the Presbyterian young [black] men in Charleston” to return to his pulpit. His sense of duty and love for “the holy city” hastened his return. As Girardeau disembarked the train in the Charleston depot the “colored members of the church” greeted their pastor with “superabounding enthusiasm.” While this does not agree with the banal image often portrayed of the Africans’ lackluster enthusiasm for white Southerners, it is no doubt true. Girardeau found a considerable number of black Carolinians anxiously awaiting his return to the pulpit.

According to a longtime friend of the Rev. John L. Girardeau, it was about this time that “[Girardeau] began to receive overtures from the Presbyterian young [black] men in Charleston” to return to his pulpit. His sense of duty and love for “the holy city” hastened his return. As Girardeau disembarked the train in the Charleston depot the “colored members of the church” greeted their pastor with “superabounding enthusiasm.” While this does not agree with the banal image often portrayed of the Africans’ lackluster enthusiasm for white Southerners, it is no doubt true. Girardeau found a considerable number of black Carolinians anxiously awaiting his return to the pulpit.

They were awaiting his return for indeed they had summoned him in a letter dated July 27, 1865. This was shortly after his grueling return from war and imprisonment. The letter speaks of their concern for Girardeau’s well-being and their desire for his return to them. It reveals a love for the man and his family that few textbooks recognize as having existed between whites and blacks, masters and slaves.

Revd Sir & pastor

We the undersigned members of Zion Presbyterian Church embrace this opportunity, as one among the many good ones we have engaged in the past and in doing so you have our best wishes for your health & that of your loving family hoping all are engaging that blessing of good health and realizing that fulfillment of good words those that put their trust in Him shall never want.

This love for Girardeau is further expressed in their longing for him to return to them and resume his pastoral labors in their midst. “The past relations,” wrote the Zion members, “we have engaged together for many years as pastor and people are still in its bud in our every heart therefore we would well come you still as our pastor.”

From the time Girardeau returned to Charleston until he was able to reoccupy the Zion pulpit, fifteen months had elapsed. Finally, “on Sabbath, December 23rd, 1866, the Rev. John L. Girardeau re-commenced services in the building.” Girardeau’s text for the occasion was “For we preach not ourselves, but Christ Jesus the Lord; and ourselves your servant for Jesus’ sake,” (2 Corinthians 4:5). While no manuscript exists of this sermon there are a few points that appear obvious. First, he preached Christ. There can be little doubt that Girardeau reminded his listeners that he had always been faithful in preaching Jesus to them. He was no moralizer or politician in the pulpit. Indeed, he may have reminded his black brothers that his catechism was replete with the gospel, without mention of master-slave relations. Second, in preaching Christ, Girardeau was also sending a message to the Northern detractors that their harassment over the past fifteen months or so was unjust. That Jonathan Gibbs (the Northern missionary) would choose the property of Zion Presbyterian Church to occupy was a clear indication that he, and by association, the Committee that sent him, did not believe the South had been adequately preaching the gospel to the African-Americans. Girardeau’s first sermon in the Zion pulpit issued a resounding “Not true!” to such an implication. Third, it would not be far-fetched to assume that Girardeau reminded his hearers that, while they were no longer slaves, he would continue to be their slave for Christ’s sake. He was not free to do otherwise.

Girardeau wasted no time rebuilding the walls of Zion. First, a meeting was held to determine the total black membership that wished to continue as Freedmen in the Zion Presbyterian Church. Much to Girardeau’s disappointment, only one hundred sixteen indicated their desire to remain in Zion. This reflected the influence of Reconstruction and the less than enthusiastic attitudes of many Southerners toward their black brothers.

Girardeau wasted no time rebuilding the walls of Zion. First, a meeting was held to determine the total black membership that wished to continue as Freedmen in the Zion Presbyterian Church. Much to Girardeau’s disappointment, only one hundred sixteen indicated their desire to remain in Zion. This reflected the influence of Reconstruction and the less than enthusiastic attitudes of many Southerners toward their black brothers.

Nevertheless, Girardeau proceeded with the one hundred sixteen faithful, and on March 25, 1867, the session nominated seven men to serve as “Superintendents” over the new congregation. The election of Superintendents, rather than elders as Girardeau desired, was in accordance with the resolution of the 1866 General Assembly. The men were all members of Zion before the war and some had served as Watchmen or Leaders of the Classes. “In 1867,” wrote Girardeau, “a fresh start in the teeth of many difficulties was made with 116 members of the 500.”

Later in the year, with Joseph B. Mack at his side, Girardeau began rebuilding the infrastructure of old Zion. The 1867 records indicate a total membership—Zion Church, Calhoun Street and Glebe Street—of four hundred forty. This included the one hundred sixteen freedmen. By March of 1868, the church had added sixty members. Fifty-one of the new additions came through profession of faith in Christ. There were nineteen infants baptized and seventeen adults. By March 1869 total communicants numbered five hundred sixty-one in Zion. Sabbath schools were once again instituted with two hundred enrolled. This number swelled to 750 scholars by 1875. While other conditions were still chaotic throughout the city, the South, and the Southern Presbyterian Church, there were some hopeful signs as evidenced by Zion.

In 1869, the General Assembly, following Girardeau’s lead, made it possible for freedmen to be ordained as elders. Just as Girardeau had quickly moved to install superintendents in the newly restored work in 1867, he wasted little time in organizing the black membership into a “branch congregation” of Zion, complete with ordained elders. On Tuesday, July 27, 1869, the Session of Zion Presbyterian Church dismissed three hundred forty-five members to form the Zion Presbyterian Church (Colored), Calhoun Street. From this we learn that in two years the black membership of Zion under the beloved white pastor had grown from one hundred sixteen to three hundred forty-five. Thus, in 1869 the black membership constituted more than one-half the total membership of Girardeau’s flock. This example offers some evidence that the integration of whites and the newly freed blacks into one church could have worked if it had been zealously pursued along the lines Girardeau recommended.

Upon the recommendation of Girardeau and the Zion Session, the following Freedmen were nominated to serve in the office of Ruling Elder—Paul Trescot, William Price, Jacky Morrison, Samuel Robinson, William Spencer, and John Warren. On “Sabbath August 15, 1869, 8 ½ P.M.” the congregation of Zion Presbyterian Church (Colored) met for worship and the ordination and installation of their Ruling Elders. Girardeau chose for his text on this occasion Acts 14: 23—“And when they had appointed for them elders in every church, and had prayed with fasting…they commended them to the Lord.” The records tell us, “Session did then with prayer and the imposition of their hands ordain the persons… and install them in the same.” Thus, Zion became the first Southern church governed by black elders. Girardeau had done what Dabney and a host of other Southern churchmen would not consider doing. He had admitted that black men could be qualified to rule in the church. He had exhibited his approbation by participating in the holy service, even the laying on of hands. What Dabney and others doubted possible, Girardeau confirmed as real.

Sadly, Girardeau’s experiment did not gain prominence in the Southern Church. In 1874, the Presbyterian Church US, under political and social pressures from within and without, voted to segregate their communion into black and white churches. Girardeau opposed the move, lost the vote, and lost his beloved Zion. Within a few short years many black Presbyterians across the South affiliated with the Presbyterian Church USA, leaving the Presbyterian Church US.

Conclusion

All human weaknesses aside, the heritage of Davies, Jones, Adger, Smyth, and Girardeau is a good one. Their sacrificial labors could and should serve as a model for many today. Our elders and deacons should adopt a paternalistic model toward the precious sheep entrusted to them by our heavenly Father. A great sensitivity and shepherd like service would follow. The men we have considered loved their black brothers and gave themselves to the good work even in the face of social, political, and ecclesiastical difficulties. No doubt there are many rejoicing in the presence of our LORD today because of the loving ministries of these men and countless others like them.

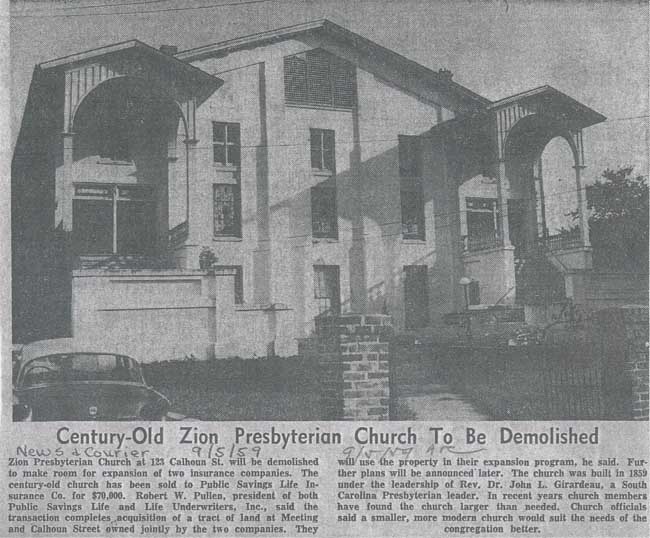

[Note: Of our two photographs of the Zion edifice, it would appear that one of the two images is reversed and does not appear as it should.]