One hundred seventy years ago, Presbyterian congregations were largely ignorant of the Church’s own Standards. Are we much better off today? Witness this quote from 1840:

“The Presbyterian Board of Publication have issued a correct edition of the Confession of Faith, and they are now selling it at the lowest possible rate, without any regard for pecuniary profit ; their principal aim being to circulate it widely through the Church.—It will be readily admitted that every Presbyterian should be at least partially acquainted with the standards of his own church, and yet how many are there who have never made these the subject of a days study? It is wholly inexcusable in pastors to have families under their care who are not provided with the Confession, especially when a little exertion on their part, might supply the defect. Will not Pastors and Sessions at once resolve that every family in the Presbyterian Church in the United States shall, before the expiration of two years, be provided with the Confession of Faith of our Church?”

[excerpted from The Charleston Observer 14.8 (11 April 1840): 2, col. 3.]

And on that note, let me next direct you to an article written a few years ago by my friend Barry Waugh. All through 2017, Mr. Waugh was writing a monthly article for his church’s website, in observation of the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation. His entry for the month of April that year was on the importance of catechism for the Reformation. He began:—

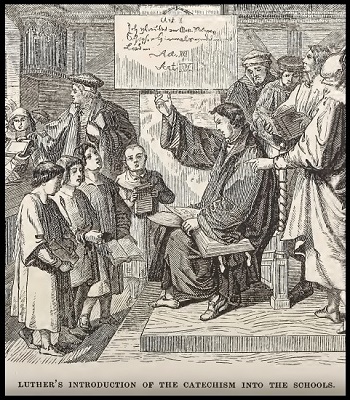

The books that would most likely come to mind for those with some knowledge of the literature of the Reformation might be Martin Luther’s The Bondage of the Will, his translation of the Bible into German, or his work on the New Testament book of Galatians. In the case of John Calvin one might think of Institutes of the Christian Religion, which was published in several editions and languages, or possibly his commentaries on many of the books of Scripture would come to mind. These works by both Luther and Calvin were written primarily for ministers, teachers, and those involved in the debates about doctrine in their era, but one of the most influential types of publications for reform was the catechism. The word “catechism” comes from the Greek language and it describes a text used for oral instruction which most often followed a question and answer format to teach essentials. In conjunction with Bibles translated into the common languages of the nations, catechisms were used to train believers in the fundamentals of faith, salvation, and Christian living. In the picture accompanying this article, Martin Luther is teaching his catechism to children in a classroom to provide them with doctrinal instruction.

In 1529, Martin Luther wrote his small catechism. It was a simple edition that included among its subjects the Ten Commandments, Apostles’ Creed, The Lord’s Prayer, other prayers including one for grace at the table, and some additional important topics for Christians. In his preface, Luther said that he wrote the catechism because during a visitation of churches in area towns he found that the people knew “nothing about Christian doctrine” and even some of the pastors were “quite unfit and incompetent to teach.” He encouraged ministers to use the catechism to teach adults but “especially … the young.” Luther’s catechism provided a concise and simple way to bring reform to a considerable portion of the people. The doctrine in Luther’s catechism is not in full agreement with that of Presbyterians today, so it is not the best source for teaching their children. In the Presbyterian Church in America (P.C.A.), the catechisms composed by the Westminster Assembly provide essential truths. However, Luther’s catechism is historically important because it provided basic instruction for the people, and it was the first catechism written by a married former Catholic priest who had children that could learn from its teaching.

To read the rest of Barry’s post, click here.