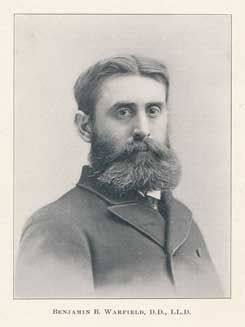

For our next several posts, we will be reviewing a powerful address by Benjamin B. Warfield, titled THE RELIGIOUS LIFE OF THEOLOGICAL STUDENTS. Dr. Warfield, who was himself a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary (class of 1876), served as Professor of Didactic and Polemic Theology there from 1887 until his death in 1921. His address on the religious life of seminary students was originally delivered before the Autumn Conference at Princeton, on October 4, 1911. Today our post will look at an opening portion of the address, in which he discusses what is called the doctrine of vocation, and while his focus is on seminary students and their call to the ministry, this same doctrine of vocation is fully applicable to the rest of us, whatever our calling in life.

For our next several posts, we will be reviewing a powerful address by Benjamin B. Warfield, titled THE RELIGIOUS LIFE OF THEOLOGICAL STUDENTS. Dr. Warfield, who was himself a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary (class of 1876), served as Professor of Didactic and Polemic Theology there from 1887 until his death in 1921. His address on the religious life of seminary students was originally delivered before the Autumn Conference at Princeton, on October 4, 1911. Today our post will look at an opening portion of the address, in which he discusses what is called the doctrine of vocation, and while his focus is on seminary students and their call to the ministry, this same doctrine of vocation is fully applicable to the rest of us, whatever our calling in life.

Perhaps the intimacy of the relation between the work of a theological student and his religious life will nevertheless bear some emphasizing. Of course you do not think religion and study incompatible. But it is barely possible that there may be some among you who think of them too much apart—who are inclined to set their studies off to one side, and their religious life off to the other side, and to fancy that what is given to the one is taken from the other. No mistake could be more gross. Religion does not take a man away from his work; it sends him to his work with an added quality of devotion. We sing—do we not?—

Teach me, my God and King,

In all things Thee to see—

And what I do in anything,

To do it as for Thee.

If done t’ obey Thy laws,

E’en servile labors shine,

Hallowed is toil, if this the cause,

The meanest work divine.

It is not just the way George Herbert wrote it. He put, perhaps, a sharper point on it. He reminds us that a man may look at his work as he looks at a pane of glass—either seeing nothing but the glass, or looking straight through the glass to the wide heavens beyond. And he tells us plainly that there is nothing so mean but that the great words, “for thy sake,” can glorify it:

A servant, with this clause,

Makes drudgery divine,

Who sweeps a room as for Thy laws,

Makes that, and the action, fine.

But the doctrine is the same, and it is the doctrine, the fundamental doctrine, of Protestant morality, from which the whole system of Christian ethics unfolds. It is the great doctrine of “vocation,” the doctrine, to wit, that the best service we can offer to God is just to do our duty—our plain, homely duty, whatever that may chance to be. The Middle Ages did not think so; they cut a cleft between the religious and the secular life, and counseled him who wished to be religious to turn his back on what they called “the world,” that is to say, not the wickedness that is in the world— “the world, the flesh and the devil,” as we say—but the work-a-day world, that congeries of occupations which forms the daily task of men and women, who perform their duty to themselves and their fellowmen. Protestantism put an end to all that. As Professor Doumergue eloquently puts it,

“Then Luther came, and, with still more consistency, Calvin, proclaiming the great idea of vocation, an idea and a word which are found in the languages of all the Protestant peoples—Beruf, Calling, Vocation—and which are lacking in the languages of the peoples of antiquity and of medieval culture. Vocation—it is the call of God, addressed to every man, whoever he may be, to lay upon him a particular work, no matter what. And the calls, and therefore also the called, stand on a complete equality with one another. The burgomaster is God’s burgomaster; the physician is God’s physician; the merchant is God’s merchant; the laborer is God’s laborer. Every vocation, liberal, as we call it, or manual, the humblest and the vilest in appearance as truly as the noblest and the most glorious, is of divine right.”

Talk of the divine right of kings! Here is the divine right of every workman, no one of whom needs to be ashamed, if only he is an honest and good workman. “Only laziness,” adds Professor Doumergue, “is ignoble, and while Romanism multiplies its mendicant orders, the Reformation banishes the idle from its towns.”

Now, as students of theology your vocation is to study theology; and to study it diligently, in accordance with the apostolic injunction: “Whatsoever ye do, do it heartily, as to the Lord.” It is precisely for this that you are students of theology; this is your “next duty,” and the neglect of duty is not a fruitful religious exercise. Dr. Charles Hodge, in his delightful auto-biographical notes, tells of Philip Lindsay, the most popular professor in the Princeton College of his day—a man sought by nearly every college in the Central States for its presidency—that “he told our class that we would find that one of the best preparations for death was a thorough knowledge of the Greek grammar.” “This,” comments Dr. Hodge, in his quaint fashion, “was his way of telling us that we ought to do our duty.” Certainly, every man who aspires to be a religious man must begin by doing his duty, his obvious duty, his daily task, the particular work which lies before him to do at this particular time and place. If this work happens to be studying, then his religious life depends on nothing more fundamentally than on just studying.

You might as well talk of a father who neglects his parental duties, of a son who fails in all the obligations of filial piety, of an artisan who systematically skimps his work and turns in a bad job, of a workman who is nothing better than an eye-servant, being religious men as of a student who does not study being a religious man. It cannot be: you cannot build up a religious life except you begin by performing faithfully your simple, daily duties. It is not the question whether you like these duties. You may think of your studies what you please. You may consider that you are singing precisely of them when you sing of “e’en servile labors,” and of “the meanest work.” But you must faithfully give yourselves to your studies, if you wish to be religious men. No religious character can be built up on the foundation of neglected duty.

Words to Live By:

Why complicate the matter? Dr. Warfield cuts through all the clutter and puts the simple truth before us: “You cannot build up a religious life except you begin by performing faithfully your simple, daily duties. . . No religious character can be built up on the foundation of neglected duty.” Here it might be important to note that when Dr. Warfield uses the word religious, we might instead use the word spiritual today. But the point stands, and should be taken to heart. More on this as Dr. Warfield continues, tomorrow.

For another examination of this message from B.B. Warfield, see the brief essay from 2014 by Dr. L. Michael Morales, chair of biblical studies at Reformation Bible College..