Today we will borrow a few paragraph from Men of the Covenant by Alexander Smellie in order to relate the story of the Third Indulgence of King James II of England. Indulgences 1 and 2 were on February 12 and March 31 of 1687. This Third Indulgence took place in London on June 28th, 1687 and then reissued on this day July 5, 1687. Smellie writes:

“King James touched nothing which he did not mismanage and spoil. His policy was a curious mixture of tyranny and toleration. A Romanist himself, he was resolved to grant new liberties to his Catholic subjects. But he dared not single them out alone for the enjoyment of favour; the country, he realized, was too fervently Protestant to permit such a preference. Of necessity he embraced other excluded folk in the largesse he distributed. In Scotland, the year 1687 saw no less that three Indulgences issued under the royal seal. These suspended ‘all penal and sanguinary laws made against any for nonconformity to the religion established by law,’ and gave sanction to His Majesty’s ‘loving subjects to meet and serve God after their own way and manner, be it in private homes, chapels, or places purposely hired or built for that use.’ Only against the Coventicler did the lightnings continue to flash forth; the Acts which Parliament had decreed for the suppression of the gatherings in the open fields were left in full force; for impenitent Cameronians it seem that there could be no whisper of mercy and no outgate into freedom. Yet here were large measures of relief which might carry in them the promise of a hopefuller era. If the followers of Renwick denounced them, there were Presbyterian ministers, in prison or banishment or hiding, who welcomed James’s Indulgences, and returned to their homes under the shelter of their provisos. But even they, profiting although they did by the altered current of affairs, had no confidence in the man who brought it about.” (p. 411)

W. M. Hetherington, author of the History of the Church of Scotland to the Period of the Disruption in 1843, picks up the account of this Third Indulgence. He writes on pg. 286 – 287: “Few were deceived by these hypocritical pretences (of the king). All true Protestants . . . perceived clearly enough, that direct favor of the Papists was intended; and it was not unfairly surmised that, by the universal toleration, the king hoped to throw the various denominations of Protestants into such a state of rivalry and collision, that they would weaken each other, and prepare for the establishment of Popery upon their ruins. There is little reason to doubt that such as his majesty’s aim and expectation; but both the immediate and the ultimate consequences were very different from what he intended and hoped. . . . In Scotland, almost all the Presbyterian ministers in the kingdom availed themselves of the opportunity which it gave them of resuming public worship, and collecting again the scattered congregations. Many, both ministers and people, returned to their long-lost homes, and engaged with renewed fervor in the reconstruction of the Presbyterian Church by the revival of its unforgotten forms of government and discipline, the reunion of its scattered but still living members, and the resuscitation of its imperishable principles.”

Words to Live By: Let us always remember that “the king’s heart is like channels of water in the hand of the LORD; He turns it wherever His wishes.” (Proverbs 21:1 NAS). Whether we live and move and have our being in a kingdom or a republic, the truth remains the same. Let us beseech our sovereign Lord to move in the hearts of those who govern our times to recognize that “righteousness exalts a nation, but sin is a disgrace to any people.” (Proverbs 14:34 NASB.)

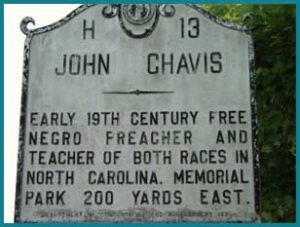

John Chavis was born in 1763 (or possibly 1762) in Granville County, North Carolina—a sparsely populated area north of Raleigh bordering Mecklenburg County, Virginia. While the details surrounding his early life and ancestry can be hazy, we know that members of the Chavis family were, along with one other family (the Harrises), the first people of African descent to be recognized as free persons in Granville County. John Chavis—whose lineage was a mix of African, American Indian, and Caucasian—came from a distinguished line of free Blacks who owned property and were committed to educating themselves as best they could. A descendant of Chavis later recalled, “My grandmother, mother, and great grandmother were all free people and Presbyterians.”

John Chavis was born in 1763 (or possibly 1762) in Granville County, North Carolina—a sparsely populated area north of Raleigh bordering Mecklenburg County, Virginia. While the details surrounding his early life and ancestry can be hazy, we know that members of the Chavis family were, along with one other family (the Harrises), the first people of African descent to be recognized as free persons in Granville County. John Chavis—whose lineage was a mix of African, American Indian, and Caucasian—came from a distinguished line of free Blacks who owned property and were committed to educating themselves as best they could. A descendant of Chavis later recalled, “My grandmother, mother, and great grandmother were all free people and Presbyterians.” After three decades of successful teaching and preaching—and, it seems, a measure of prosperity from dabbling in real estate—Chavis saw his ministry (and his money) dry up in the 1830s. In 1832, in response to Nat Turner’s Rebellion of August 1831, the North Carolina legislature made it unlawful for any free person of color to preach or exhort in public or to officiate as a preacher. Chavis pleaded with the Presbytery for financial support, but the collection they took was little more than $50. In an effort to pay his bills and provide for his wife and children (about whom we know next to nothing), he requested in 1832 that the Presbytery publish his Letter Upon the Doctrine of the Extent of the Atonement of Christ. The Presbytery denied the request, arguing that the subject had already been dealt with by others and there was little chance the short pamphlet would produce much income. No doubt, the Presbytery also demurred because Chavis had drifted from confessional Reformed orthodoxy. In the Letter, Chavis argued that the free offer of the gospel was inconsistent with limited atonement and that the eternal decrees of God were based on “nothing more nor less than his foreknowledge.” Judging by his Letter, Chavis was a passionate gospel preacher who aligned with the New School wing of the Presbyterian controversies of the 1830s.

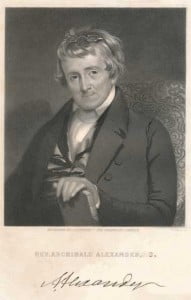

After three decades of successful teaching and preaching—and, it seems, a measure of prosperity from dabbling in real estate—Chavis saw his ministry (and his money) dry up in the 1830s. In 1832, in response to Nat Turner’s Rebellion of August 1831, the North Carolina legislature made it unlawful for any free person of color to preach or exhort in public or to officiate as a preacher. Chavis pleaded with the Presbytery for financial support, but the collection they took was little more than $50. In an effort to pay his bills and provide for his wife and children (about whom we know next to nothing), he requested in 1832 that the Presbytery publish his Letter Upon the Doctrine of the Extent of the Atonement of Christ. The Presbytery denied the request, arguing that the subject had already been dealt with by others and there was little chance the short pamphlet would produce much income. No doubt, the Presbytery also demurred because Chavis had drifted from confessional Reformed orthodoxy. In the Letter, Chavis argued that the free offer of the gospel was inconsistent with limited atonement and that the eternal decrees of God were based on “nothing more nor less than his foreknowledge.” Judging by his Letter, Chavis was a passionate gospel preacher who aligned with the New School wing of the Presbyterian controversies of the 1830s. Archibald Alexander had been prepared by the Holy Spirit for this important ministry. Blessed with an heritage of Scotch-Irish forefathers, and a father who was a Presbyterian elder, his family first settled in Pennsylvania before relocating to Virginia. Archibald was born in 1772 and by the age of seven, had learned the Shorter Catechism and was moving on to the Larger Catechism. He sat under the celebrated William Graham at Liberty Hall Academy, forerunner of Washington and Lee College. And yet with all of this training, Archibald was still unsaved. It wasn’t until he was sixteen that he was brought to a saving knowledge of the Lord Jesus. More theological training took place which culminated in his ordination by Hanover Presbytery in Virginia in 1794 as a Presbyterian minister.

Archibald Alexander had been prepared by the Holy Spirit for this important ministry. Blessed with an heritage of Scotch-Irish forefathers, and a father who was a Presbyterian elder, his family first settled in Pennsylvania before relocating to Virginia. Archibald was born in 1772 and by the age of seven, had learned the Shorter Catechism and was moving on to the Larger Catechism. He sat under the celebrated William Graham at Liberty Hall Academy, forerunner of Washington and Lee College. And yet with all of this training, Archibald was still unsaved. It wasn’t until he was sixteen that he was brought to a saving knowledge of the Lord Jesus. More theological training took place which culminated in his ordination by Hanover Presbytery in Virginia in 1794 as a Presbyterian minister.