“Ye shall be My witnesses”

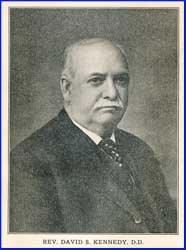

Our post today is from an editorial by the Rev. David S. Kennedy, who served as the editor of THE PRESBYTERIAN, a Philadelphia-based magazine of long standing. Rev. Kennedy’s associate editor at this time and later successor in that post was the Rev. Samuel Craig, who went on to found the Presbyterian & Reformed Publishing Company. Rev. Kennedy’s editorial was written and appeared during the pitch of the modernist controversy.

Our post today is from an editorial by the Rev. David S. Kennedy, who served as the editor of THE PRESBYTERIAN, a Philadelphia-based magazine of long standing. Rev. Kennedy’s associate editor at this time and later successor in that post was the Rev. Samuel Craig, who went on to found the Presbyterian & Reformed Publishing Company. Rev. Kennedy’s editorial was written and appeared during the pitch of the modernist controversy.

The Main Function of the Church

[The Presbyterian 95.26 (25 June 1925): 3-4.]

THE church of Jesus Christ has many functions. Among these functions, however, there is one that takes precedence of all others. This function was given initial and summary expression by the supreme Head of the church himself immediately after his ascension and his resumption of that glory which he had had with the Father before the world was — in what were therefore the final instructions he gave to his church — in person rather than through the instrumentality of his apostles — in the words that are recorded in the eighth verse of the first chapter of the Book of Acts, “Ye shall be my witnesses both in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and unto the uttermost parts of the earth.”

The primary function of the church is to bear witness, to make known its message of truth. The campaign launched by the apostles, at the command of Christ himself, was a campaign of witnessing. It was by the “foolishness of preaching” that they began the task, not only of bringing the thoughts and activities of individuals into captivity to their Lord, but of transforming the kingdoms of this world into his kingdom. It is not strange that it seemed foolishness to the then-living wise of this world that the apostles should expect to achieve any significant results by the use of such a method. One might think that the history of the last nineteen hundred years had abundantly justified the wisdom of their method; and yet there are still many, even within the Christian church, to whom the method seems foolish to such a degree that they have largely subordinated it to other methods. For the “foolishness of preaching” they substitute organization, mass movements, programmes, and such like, so that instead of being primarily “men with a message,” they are rather “men with a programme.” Plans and programmes and organizations have an important part to play in the great task of Christianizing the world, but in view of the method commended by Christ himself and followed by the apostles, it is clear that our chief dependence should be on the purity and sincerity of our testimony to the truth as it is in Jesus Christ.

From the very beginning the campaign of witnessing carried on by the apostles included two elements — both of which were kept constantly in the foreground. In the first place, they made known what had taken place, the great historical events that lie at the basis of the Christian religion. In the second place, they expounded the meaning and significance of those facts or events.

The apostles were not mere philosophers, expounders and defenders of certain religious ideas which they had been led to adopt through their association with the great Nazarene teacher; neither were they mere ethical teachers, those primarily interested in leading men to accept certain ethical or moral ideals that would lead them to live as Jesus lived. Certainly they were religious and ethical teachers who urged men to take Jesus as their example, but primarily they were concerned about telling men of certain events that had happened and of the meaning and significance of those events. “I delivered unto you first of all that which I also received,” wrote Paul, “that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures; and that he was buried; and that he hath been raised on the third day according to the Scriptures.” They testified to the facts, in the sense of events that have happened, that lie at the basis of the gospel — apart from which there would be no gospel. They told, men that Christ had died and that he had risen. That was not all, however. They also pointed out the meaning of those facts — that Jesus had died “for our sins,” and that he was “raised for our justification.” They did not suppose that the facts alone—what are sometimes called the “bare or naked” facts, that is, the facts apart from any interpretation of them—gave them a gospel of redemption to proclaim. It is more than questionable whether we can conceive such a thing as a “bare” or “naked” fact, but it is at least certain that such a fact would be meaningless. It is true that apart from such facts as the death and resurrection of Jesus there would be no gospel for a sin cursed world; but it is equally true that there would be no such gospel if the meaning and significance of those facts were not known. Only as we realize that the death and resurrection of Jesus was the death and resurrection of the God-man, and that he was “delivered for our trespasses and raised for our justification,” do they beget in us a living hope concerning “an inheritance incorruptible, and undefiled, and that fadeth not away.” In other words, the gospel is constituted, not by facts apart from doctrines, still less by doctrines apart from facts, but by facts and doctrines, so bound together that in effect they coalesce. As the late James Orr, to whose writings so many of this generation are indebted, once put it: “The gospel is no mere proclamation of ‘eternal truths,’ but the discovery of a saving purpose of God for mankind, executed in time. But the doctrines are the interpretation of the facts. The facts do not stand blank and dumb before us, but have a voice given them and a meaning put into them. They are accompanied by living speech, which makes their meaning clear. When John declares that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh and is the Son of God, he is stating a fact, but he is none the less enunciating a doctrine. When Paul affirms, ‘Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures,’ he is proclaiming a fact, but he is at the same time giving an interpretation of it.”

It is impossible for the church of Jesus Christ to adequately function in the world except as it bears clear and positive testimony to the facts and doctrines of the Christian religion. After all, the fundamental thing about Christianity is that it is a revelation of truth. From the Christian viewpoint, therefore, there can be no greater evil than the evil of compromising with truth or even of minimizing the value and importance of truth. Neglect or even ascribe a secondary place to the truth as it is in Jesus, and the main purpose for which the church exists is surrendered.

If the church is functioning badly to-day, it is largely because of the evid [?] of divided conviction and divided testimony. The testimony given throughout the church is discordant and contradictory. What one minister commends as saving truth, another minister denounces as fatal error. Is it any wonder that the rank and file are distracted and confused? There is no more pressing need than the bringing about of a situation wherein the church, as far as is humanly possible, will bear undivided testimony to the gospel of the grace of God in its purity. In as far as such divided testimony exists within the Presbyterian Church, it largely finds its explanation in the fact that men have been admitted to its ministry — or have persisted in remaining in its ministry — in defiance of its constitutional requirements. The recent judicial decision makes clear that, according to the Constitution, only those who have “clear and positive” views as to Christian doctrines are eligible for licensure. “’The presbytery must be satisfied,” so the decision reads, ”that the applicant is clear and positive in his belief as to the doctrines of the church, and unless he is thus clear and positive, it is the duly of presbytery to defer licensure until he becomes clear and positive.” It is clear, of course, that if those lacking clear and positive beliefs as to the doctrines of the church have no right to enter the Presbyterian ministry, such have also no right to remain in this ministry. This action of the General Assembly, it need scarcely be said, added nothing to the Constitution of the Presbyterian Church; it merely gave clear and definitive expression to what was already in the Constitution, but which in some quarters was being ignored or even denied.