This paper was read before a group of ministers in Philadelphia on November 27, 1933. It was subsequently published in Christianity Today (August 1934) and in a collection of Machen’s essays edited by Ned B. Stonehouse, published under the title What Is Christianity? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1951). The address was again separately reprinted in 2002 by the Committee for the Historian of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church and can also be found online at the OPC website : http://www.opc.org/machen/mountains.html.

Mountains and Why We Love Them

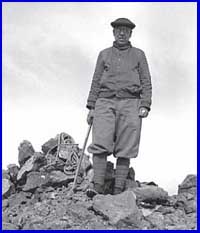

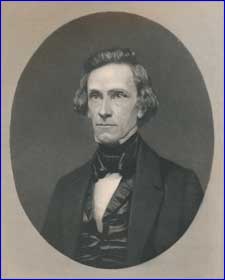

by J. Gresham Machen

What right have I to speak about mountain-climbing? The answer is very simple. I have none whatever. I have, indeed, been in the Alps four times. The first time I got up Monte Rosa, the second highest of the Alps, and one or two others of the easier Zermatt peaks. On my second visit I had some glorious days in the Grossglockner group and on a few summits in the Zillerthal Alps and also made my first visit to that beautiful liberty-loving land of South Tirol, where, as a result of a war fought to “make the world safe for democracy,” Mussolini is now engaged in the systematic destruction of a language and civilization that has set its mark upon the very face of the landscape for many centuries. On my third visit, in 1913, I did my most ambitious climbing, all in the Eastern Alps, getting up the Kleine Zinne by the north face, certain of the sporty Cortina courses, and also the Campanile di Val Montanaia, which is not considered altogether easy. In 1932 I was on three of the first-class Zermatt peaks.

What right have I to speak about mountain-climbing? The answer is very simple. I have none whatever. I have, indeed, been in the Alps four times. The first time I got up Monte Rosa, the second highest of the Alps, and one or two others of the easier Zermatt peaks. On my second visit I had some glorious days in the Grossglockner group and on a few summits in the Zillerthal Alps and also made my first visit to that beautiful liberty-loving land of South Tirol, where, as a result of a war fought to “make the world safe for democracy,” Mussolini is now engaged in the systematic destruction of a language and civilization that has set its mark upon the very face of the landscape for many centuries. On my third visit, in 1913, I did my most ambitious climbing, all in the Eastern Alps, getting up the Kleine Zinne by the north face, certain of the sporty Cortina courses, and also the Campanile di Val Montanaia, which is not considered altogether easy. In 1932 I was on three of the first-class Zermatt peaks.

Why, then, have I no right to talk about mountain-climbing? For the simple reason that I did all of these climbs with good guides, safeguarded by perfectly good Alpine ropes. An Alpine guide is said to be able to get a sack of meal up the Matterhorn about as well as he can get some tourists up, and then those tourists go home and boast what great mountaineers they are. Well, I differed from the proverbial sack of meal in two particulars: (1) I am a little superior to the sack of meal in climbing ability; (2) the sack of meal is unaware of the fact that it is not a mountaineer, and I am fully aware of the fact that I am not. The man who leads on the rope is the man who has to be a real mountaineer, and I never did that. I am less than the least of the thousands of real climbers who go to the Alps every summer and climb without guides.

But although I am not a mountaineer, I do love the mountains and I have loved them ever since I can remember anything at all. It is about the love of the mountains, rather than about the mountains, that I am venturing to read this little paper today.

Can the love of the mountains be conveyed to those who have it not? I am not sure. Perhaps if a man is not born with that love it is almost as hopeless to try to bring it to him as it would be to explain what color is to a blind man or to try to make President Roosevelt understand the Constitution of the United States. But on the whole I do believe that the love of the mountains can at least be cultivated, and if I can do anything whatever toward getting you to cultivate it, the purpose of this little paper will be amply attained.

One thing is clear—if you are to learn to love the mountains you must go up them by your own power. There is more thrill in the smallest hill in Fairmount Park if you walk up it than there is in the grandest mountain on earth if you go up it in an automobile. There is one curious thing about means of locomotion—the slower and simpler and the closer to nature they are, the more real thrill they give. I have got far more enjoyment out of my two feet than I did out of my bicycle; and I got more enjoyment out of my bicycle than I ever have got out of my motor car; and as for airplanes—well, all I can say is that I wouldn’t lower myself by going up in one of the stupid, noisy things! The only way to have the slightest inkling of what a mountain is is to walk or climb up it.

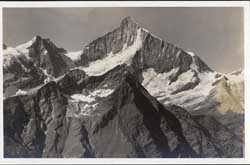

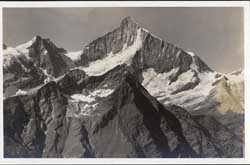

The Mettelhorn in the foreground, 4192 m., & in the background, the Weisshorn, 4512 m.

Now I want you to feel something of what I feel when I am with the mountains that I love. To that end I am not going to ask you to go with me to any out-of-the-way place, but I am just going to take you to one of the most familiar tourist’s objectives, one of the places to which one goes on every ordinary European tour—namely, to Zermatt—and in Zermatt I am not going to take you on any really difficult climbs but merely up one or two of the peaks by the ordinary routes which modern mountaineers despise. I want you to look at Zermatt for a few minutes not with the eyes of a tourist, and not with the eyes of a devotee of mountaineering in its ultra-modern aspects, but with the eyes of a man who, whatever his limitations, does truly love the mountains.

In Zermatt, after I arrived on July 15, 1932, I secured Alois Graven as my guide; and on a number of the more ambitious expeditions I had also Gottfried Perren, who also is a guide of the first class. What Ty Cobb was on a baseball diamond and Bill Tilden is on the courts, that such men are on a steep snow or ice slope, or negotiating a difficult rock, Ueberhang. It is a joy as I have done in Switzerland and in the Eastern Alps, to see really good climbers at work.

At this point I just want to say a word for Swiss and Austrian guides. Justice is not done to them, in my judgment, in many of the books on climbing. You see, it is not they who write the books. They rank as professionals, and the tourists who hire them as “gentleman”; but in many cases I am inclined to think that the truer gentleman is the guide. I am quite sure that that was the case when I went with Alois Graven.

In addition to climbing practice on the wrong side of the cocky little Riffelhorn and on the ridge of the Untergabelhorn—which climbing practice prevented me from buttoning my back collar button without agony for a week—and in addition to an interesting glacier expedition around the back side of the Breithorn and up Pollux (13,430 feet) and Caster (13,850) and down by the Fellikjoch through the ice fall of the Zwillingsgletscher, on which expedition I made my first acquaintance with really bad weather in the high Alps and the curious optical illusions which it causes—it was perfectly amazing to see the way in which near the summit of Caster the leading guide would feel with his ice-axe for the edge of the ridge in what I could have sworn to be a perfectly innocent expanse of easy snowfield right there in plain view before our feet, and it was also perfectly amazing to see the way in which little pieces of ice on the glacier were rolled by way of experimentation down what looked like perfectly innocent slopes, to see whether they would simply disappear in crevasses which I could have sworn not to be there (if they disappeared we didn’t because we took the hint and chose some other way through the labyrinth)—after these various preliminary expeditions and despite the agony of a deep sore on my right foot in view of which the Swiss doctor whom I consulted told me that as a physician he would tell me to quit but that as a man he knew I would not do so and that therefore he would patch me up as well as possible, and despite the even greater agony of a strained stomach muscle which I got when I extricated myself and was extricated one day from a miniature crevasse and which made me, the following night in the Theodul hut, feel as helpless as a turtle laid on its back, so that getting out of my bunk became a difficult mountaineering feat—after these preliminary expeditions and despite these and other agonies due to a man’s giving a fifty-year-old body twenty-year-old treatment, I got up three first-class Zermatt peaks; the Zinalrothorn, the Matterhorn, and the Dent Blanche. Of these three, I have not time—or rather you have not time (for I for my part should just love to go on talking about the mountains for hours and Niagara would have nothing on me for running on)—I say, of these you have not time for me to tell about more than one. It is very hard for me to choose among the three. The Zinalrothorn, I think, is the most varied and interesting as a climb; the Dent Blanche has always had the reputation of being the most difficult of all the Zermatt peaks, and it is a glorious mountain indeed, a mountain that does not intrude its splendors upon the mob but keeps them for those who will penetrate into the vastnesses or will mount to the heights whence true nobility appears in its real proportions. I should love to tell you of that crowning day of my month at Zermatt, when after leaving the Schönbühl Hut at about 2.30 A.M. (after a disappointment the previous night when my guides had assisted in a rescue expedition that took one injured climber and the body of one who was killed in an accident on the Zmutt Ridge of the Matterhorn, opposite the hut where we were staying, down to Zermatt so that we all arrived there about 2 A.M., about the time when it had been planned that we should leave the hut for our climb) we made our way by lantern light up into the strange upper recesses of the Schönbühl Glacier, then by the dawning light of the day across the glacier, across the bottom of a couloir safe in the morning but not a place where one lingers when the warmth of afternoon has affected the hanging glacier two thousand feet above, then to the top of the Wandfluh, the great south ridge, at first broad and easy but contracting above to its serrated knife-edge form, then around the “great gendarme” and around or over the others of the rock towers on the ridge, until at last that glorious and unbelievable moment came when the last few feet of the sharp snow ridge could be seen with nothing above but a vacancy of blue, and when I became conscious of the fact that I was actually standing on the summit of the Dent Blanche.

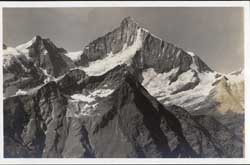

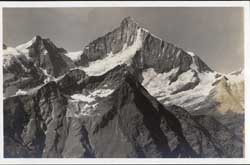

The Matterhorn, 4505 m. and Dent d’Herens, 4180.

But the Matterhorn is a symbol as well as a mountain, and so I am going to spend the few minutes that remain in telling you about that.

There is a curious thing when you first see the Matterhorn on a fresh arrival at Zermatt. You think your memory has preserved for you an adequate picture of what it is like. But you see that you were wrong. The reality is far more unbelievable than any memory of it can be. A man who sees the Matterhorn standing at that amazing angle above the Zermatt street can believe that such a thing exists only when he keeps his eyes actually fastened upon it.

When I arrived on July 15, 1932, the great mountain had not yet been ascended that summer. The masses of fresh snow were too great; the weather had not been right. That is one way in which this mountain retains its dignity even in the evil days upon which it has fallen when duffers such as I can stand upon its summit. In storm, it can be almost as perilous as ever even to those who follow the despised easiest route.

It was that despised easiest route, of course, which I followed—though my guide led me to have hopes of doing the Zmutt Ridge before I got through. On Monday, August 1st, we went up to the “Belvedere,” the tiny little hotel (if you can call it such) that stands right next to the old Matterhorn Hut at 10,700 feet. We went up there intending to ascend the Matterhorn the next day. But alas for human hopes. Nobody ascended the Matterhorn the next day, nor the day after that, nor that whole week. On Wednesday we with several other parties went a little way, but high wind and cold and snow soon drove us back. The Matterhorn may be sadly tamed, but you cannot play with it when the weather is not right. That applies to experts as well as to novices like me. I waited at the Belvedere all that week until Friday. It is not the most comfortable of summer resorts, and I really think that the stay that I made in it was one of the longest that any guest had ever made. Its little cubby-holes of rooms are admirable as Frigidaires, but as living quarters they are “not so hot.” People came and people went; very polyglot was the conversation: but I remained. I told them that I was the hermit or the Einsiedler of the Belvedere. At last, however, even I gave it up. On Friday I returned to Zermatt, in plenty of time for the Saturday night bath!

The next Monday we toiled again up that five thousand feet to the Belvedere, and this time all went well. On Tuesday, August 9th, I stood on what I suppose is, next to Mt. Everest, the most famous mountain in the world.

From the Belvedere to the summit is about four thousand feet. The Matterhorn differs from every other great Alpine peak that I know anything about in that when you ascend it by the usual route you do not once set foot on a glacier. You climb near the northeast ridge—for the most part not on the actual ridge itself but on the east face near the ridge. In some places in the lower part there is some danger from falling stones, especially if other parties are climbing above. There is scarcely anything that the blasé modern mountaineer calls rock climbing of even respectable difficulty; but it is practically all rock climbing or clambering of a sort, and it seems quite interesting enough to the novice. The most precipitous part is above what is called “the shoulder,” and it was from near this part that the four members of Whymper’s party fell 4,000 feet to their death when they were descending after the first ascent in 1865. There are now fixed ropes at places in this part. You grasp the hanging rope with one hand and find the holds in the rock with the other. It took me five hours and forty minutes to make the ascent from the Belvedere. It would certainly have been no great achievement for an athlete; but I am not an athlete and never was one, and I was then fifty-one years of age and have an elevator in the building where I live. The rarefied air affected me more than it used to do in my earlier years, and the mountain is about 14,700 feet high. I shall never forget those last few breathless steps when I realized that only a few feet of easy snow separated me from the summit of the Matterhorn. When I stood there at last—the place where more than any other place on earth I had hoped all my life that I might stand—I was afraid I was going to break down and weep for joy.

The summit of the Matterhorn (Mont Cervin)

The summit looks the part. It is not indeed a peak, as you would think it was from looking at the pictures which are taken from Zermatt, but a ridge—a ridge with the so-called Italian summit at one end and the so-called Swiss summit three feet higher at the other. Yes, it is a ridge. But what a ridge! On the south you look directly over the stupendous precipice of the south face to the green fields of Valtournanche. On the north you look down an immensely steep snow slope—with a vacancy beyond that is even more impressive than an actual view over the great north precipice would be. As for the distant prospect, I shall not try to describe it, for the simple reason that it is indescribable. Southward you look out over the mysterious infinity of the Italian plain with the snows of Monte Viso one hundred miles away. To the west, the great snow dome of Mont Blanc stands over a jumble of snow peaks; and it looks the monarch that it is. To the north the near peaks of the Weisshorn and the Dent Blanche, and on the horizon beyond the Rhone Valley a marvelous glittering galaxy of the Jungfrau and the Finsteraarhorn and the other mountains of the Benese Oberland. To the east, between the Strahlhorn and Monte Rosa, the snows of the Weissthorn are like a great sheet let down from heaven, exceeding white and glistering, so as no fuller on earth can white them; and beyond, fold on fold, soft in the dim distance, the ranges of the Eastern Alps.

Then there is something else about that view from the Matterhorn. I felt it partly at least as I stood there, and I wonder whether you can feel it with me. It is this. You are standing there not in any ordinary country, but in the very midst of Europe, looking out from its very centre. Germany just beyond where you can see to the northeast, Italy to the south, France beyond those snows of Mont Blanc. There, in that glorious round spread out before you, that land of Europe, humanity has put forth its best. There it has struggled; there it has fallen; there it has looked upward to God. The history of the race seems to pass before you in an instant of time, concentrated in that fairest of all the lands of the earth. You think of the great men whose memories you love, the men who have struggled there in those countries below you, who have struggled for light and freedom, struggled for beauty, struggled above all for God’s Word. And then you think of the present and its decadence and its slavery, and you desire to weep. It is a pathetic thing to contemplate the history of mankind.

I know that there are people who tell us contemptuously that always there are croakers who look always to the past, croakers who think that the good old times are the best. But I for my part refuse to acquiesce in this relativism which refuses to take stock of the times in which we are living. It does seem to me that there can never be any true advance, and above all there can never be any true prayer, unless a man does pause occasionally, as on some mountain vantage ground, to try, at least, to evaluate the age in which he is living. And when I do that, I cannot for the life of me see how any man with even the slightest knowledge of history can help recognizing the fact that we are living in a time of sad decadence—a decadence only thinly disguised by the material achievements of our age, which already are beginning to pall on us like a new toy. When Mussolini makes war deliberately and openly upon democracy and freedom, and is much admired for doing so even in countries like ours; when an ignorant ruffian is dictator of Germany, until recently the most highly educated country in the world—when we contemplate these things I do not see how we can possibly help seeing that something is radically wrong. Just read the latest utterances of our own General Johnson, his cheap and vulgar abuse of a recent appointee of our President, the cheap tirades in which he develops his view that economics are bunk—and then compare that kind of thing with the state papers of a Jefferson or a Washington—and you will inevitably come to the conclusion that we are living in a time when decadence has set in on a gigantic scale.

What will be the end of that European civilization, of which I had a survey from my mountain vantage ground—of that European civilization and its daughter in America? What does the future hold in store? Will Luther prove to have lived in vain? Will all the dreams of liberty issue into some vast industrial machine? Will even nature be reduced to standard, as in our country the sweetness of the woods and hills is being destroyed, as I have seen them destroyed in Maine, by the uniformities and artificialities and officialdom of our national parks? Will the so-called “Child Labor Amendment” and other similar measures be adopted, to the destruction of all the decencies and privacies of the home? Will some dreadful second law of thermodynamics apply in the spiritual as in the material realm? Will all things in church and state be reduced to one dead level, coming at last to an equilibrium in which all liberty and all high aspirations will be gone? Will that be the end of all humanity’s hopes? I can see no escape from that conclusion in the signs of the times; too inexorable seems to me to be the march of events. No, I can see only one alternative. The alternative is that there is a God—a God who in His own good time will bring forward great men again to do His will, great men to resist the tyranny of experts and lead humanity out again into the realms of light and freedom, great men, above all, who will be messengers of His grace. There is, far above any earthly mountain peak of vision, a God high and lifted up who, though He is infinitely exalted, yet cares for His children among men.

What have I from my visits to the mountains, not only from those in the Alps, but also, for example, from that delightful twenty-four-mile walk which I took one day last summer in the White Mountains over the whole Twin Mountain range? The answer is that I have memories. Memory, in some respects, is a very terrible thing. Who has not experienced how, after we have forgotten some recent hurt in the hours of sleep, the memory of it comes back to us on our awaking as though it were some dreadful physical blow. Happy is the man who can in such moments repeat the words of the Psalmist and who in doing so regards them not merely as the words of the Psalmist but as the Word of God. But memory is also given us for our comfort; and so in hours of darkness and discouragement I love to think of that sharp summit ridge of the Matterhorn piercing the blue or the majesty and the beauty of that world spread out at my feet when I stood on the summit of the Dent Blanche.

Words to Live By:

God will, in His own good time, bring forward great men again to do His will, great men who will resist the tyranny of experts and lead humanity out again into the realms of light and freedom, great men, above all, who will be messengers of His grace. There is, far above any earthly mountain peak of vision, a God high and lifted up who, though He is infinitely exalted, yet cares for His children among men.

Image sources: The images from the Alps are scanned from postcards sent back by Dr. Machen in a letter to Dr. Allan A. MacRae. To read more about this address by Dr. Machen, click here.

As the General Secretary of the Independent Board, Rev. Woodbridge composed, on behalf of the Independent Board, a “Statement as to Its Organization and Program.” The text that follows is a portion of that Statement:—

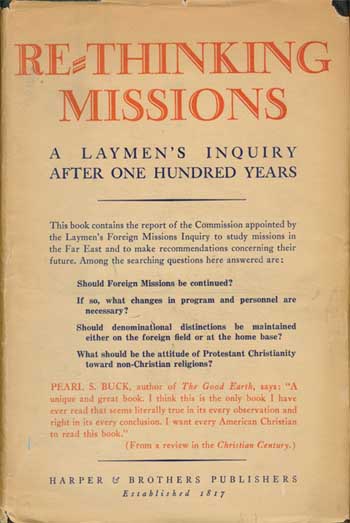

As the General Secretary of the Independent Board, Rev. Woodbridge composed, on behalf of the Independent Board, a “Statement as to Its Organization and Program.” The text that follows is a portion of that Statement:— When the Laymen’s Appraisal Commission’s Report was issued last year, an attack against the very heart of the Christian message, the Board, instead of swiftly, directly, and uncompromisingly repudiating the Report, answered it in terms which were most vague and unsatisfactory.

When the Laymen’s Appraisal Commission’s Report was issued last year, an attack against the very heart of the Christian message, the Board, instead of swiftly, directly, and uncompromisingly repudiating the Report, answered it in terms which were most vague and unsatisfactory.