We are pleased to begin today our series on Election Day Sermons, authored by the Rev. David W. Hall, pastor of the Midway Presbyterian Church, Powder Springs, Georgia. This series will post every Saturday and will run through most of this year, concluding at the end of October. We had originally intended to post the first segment next Saturday, January 30th, just prior to the Iowa Caucus, but Dr. Hall thought the following to be timely, and so we begin the series today. The last post in the series should appear approximately right before Election Day in November of this year.

A Sermon on the Anniversary of the Independence of America by Samuel Miller (July 4, 1793)

by Dr. David W. Hall

On January 18th at Liberty University, a Republican candidate referred to a Bible passage in his talk (and was criticized for wrongly citing it—although some scholars would agree that “2 Corinthians” is as acceptable as “Second Corinthians” as far as phraseology goes, but we doubt that Mr. Trump was aware of those nuances), advising that Christianity was under siege. While such remarks stir our passions, more than two centuries earlier, another speaker referred to that same passage with an entire sermon devoted to it. If one wishes a more thorough explication of this passage, one could consult Samuel Miller’s “Sermon on the Anniversary of the Independence of America.” Perhaps even Mr. Trump would benefit from a more detailed acquaintance with this classic sermon.

If one doesn’t believe that earlier American preachers frequently preached politically-ladened material, he is simply not aware of history. In this 1793 memorial sermon, a youthful stalwart from Princeton chose the text from 2 Cor. 3:17 (“And where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is Liberty”) to remind his listeners of the blessings of liberty. He addressed them as “near witnesses of these stupendous transactions,” even though the events were well known. He set the stage with this well-stated opening:

In contemplating national advantages, and national happiness, numerous are the objects which present themselves to a wise and reflecting patriot. While he remembers the past, with thankfulness and triumph; and while he looks forward, with glowing anticipation, to future glories, he will by no means forget to inquire into the secret springs, which had an active influence in the former, and which, there is reason to believe, will be equally connected with the latter.

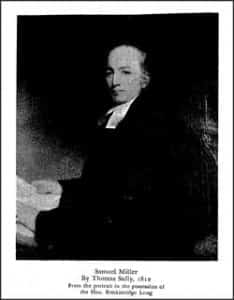

Samuel Miller (1769-1850) was the second Professor at Princeton Seminary (NJ) beginning in 1813. Ordained in 1793, he pastored several churches in New York City (Wall Street and First Presbyterian Churches) The author of numerous theological and ecclesiological texts, Miller is viewed as a co-founder of Princeton Seminary (1813), becoming the pedagogical guiding light for the likes of Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, and others. His interests ranged from theater to slavery, and from history to government. He also served as Moderator of the Presbyterian General Assembly. He is a distinct link between the Colonial era and the nineteenth century.

Samuel Miller (1769-1850) was the second Professor at Princeton Seminary (NJ) beginning in 1813. Ordained in 1793, he pastored several churches in New York City (Wall Street and First Presbyterian Churches) The author of numerous theological and ecclesiological texts, Miller is viewed as a co-founder of Princeton Seminary (1813), becoming the pedagogical guiding light for the likes of Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, and others. His interests ranged from theater to slavery, and from history to government. He also served as Moderator of the Presbyterian General Assembly. He is a distinct link between the Colonial era and the nineteenth century.

Miller wishes to offer “a few general remarks on the important influence of the Christian religion in promoting political freedom.” Fully cognizant of the original setting and meaning of this passage in Corinthians, notwithstanding, Miller believed that “the proposition contained in our text is equally true, whether we understand it as speaking of spiritual or political liberty, we may safely apply it to the latter, without incurring the charge of unnatural perversion.” Far from hesitating to apply this ancient text to his moment, he preached:

The sentiment, then, which I shall deduce from the text, and to illustrate and urge which, shall be the principal object of the present discourse, is, That the general prevalence of real Christianity, in any government, has a direct and immediate tendency to promote, and to confirm therein, political liberty.

This important truth may be established, both by attending to the nature of this religion, in an abstract view; and by adverting to fact, and the experimental testimony with which we are furnished by history.

Like Calvin before him, Miller still spoke of human depravity and referred to “tyranny” (used 6 times in this sermon) as the causative enemy both to be avoided and which justified rebellion. Further, political liberty did not automatically flow from consent of the governed, dispersed governmental branches, nor did “political liberty . . . rest, solely, on the form of government, under which a nation may happen to live.” Instead, “It must have its seat in the hearts and dispositions of those individuals which compose the body politic; and it is with the hearts and dispositions of men that Christianity is conversant.” Thus, enduring liberty, “that perfect law of liberty, which this holy religion includes, prevails and governs in the minds of all, their freedom rests upon a basis more solid and immovable, than human wisdom can devise. For the obvious tendency of this divine system, in all its parts, is, in the language of its great Author, to bring deliverance to the captives, and the opening of the prison to them that are bound; to undo the heavy burdens; to let the oppressed go free; and to break every yoke.”

With piercing specificity, he claimed: “The prevalence of real Christianity, tends to promote the principles and the love of political freedom, by the doctrines which it teaches, concerning the human character, and the unalienable rights of mankind; and by the virtues which it inculcates, and leads its votaries to practice.” A correlate of this biblical faith was:

Christianity, on the one hand, teaches those, who are raised to places of authority, that they are not intrinsically greater than those whom they govern; and that all the rational and justifiable power with which they are invested, flows from the people, and is dependent on their sovereign pleasure. There is a love of dominion natural to every human creator; and in those who are destitute of religion, this temper is apt to reign uncontrolled. Hence experience has always testified, that rulers, left to themselves, are prone to imagine, that they are a superior order of beings . . .

In contrast to the religion of self,

Christianity, wherever it exerts its native influence, leads every citizen to reverence himself-to cherish a free and manly spirit-to think with boldness and energy-to form his principles upon fair inquiry, and to resign neither his conscience nor his person to the capricious will of men. It teaches, and it creates in the mind, a noble contempt for that abject submission to the encroachments of despotism, to which the ignorant and the unprincipled readily yield. It forbids us to call, or to acknowledge, any one master upon earth, knowing that we have a Master in heaven, to whom both rulers, and those whom they govern, are equally accountable. In a word, Christianity, by illuminating the minds of men, leads them to consider themselves, as they really are, all coordinate terrestrial princes, stripped, indeed, of the empty pageantry and title, but retaining the substance of dignity and power. Under the influence of this illumination, how natural to disdain the shackles of oppression-to take the alarm at every attempt to trample on their just rights; and to pull down, with indignation, from the seat of authority, every bold invader!

One of Miller’s clearest summaries asserts: “The prevalence of Christianity promotes the principles and the love of political freedom, not only by the knowledge which it affords of the human character, and of the unalienable rights of mankind, but also by the duties which it inculcates, and leads its votaries to discharge.” Further, he sees “the native tendency of the Christian religion” as promoting “civil liberty.” Miller adds: “When we compare those nations, in which Christianity was unknown, with those which have been happily favored with the light of spiritual day, we find ample reason to justify the remarks which have been made.”

Miller not only extols the value of religion for the public square but also he claimed that “there never was a government, in which the knowledge of pure and undefiled Christianity prevailed, in which, at the same time, despotism held his throne without control.” As a specific, Miller thought Christianity mitigated against slavery, which yielded “to the mild and benign spirit of Christianity. Experience has shown, that domestic slavery also flies before her, unable to stand the test of her pure and holy tribunal. After the introduction of this religion into the Roman empire, every law that was made, relating to slaves, was in their favor, abating the rigors of servitude, until, at last, all the subjects of the empire were reckoned equally free.” He also expected that “Christianity shall extend her scepter of benevolence and love over every part of this growing empire-when oppression shall not only be softened of his rigors; but shall take his flight forever from our land.”

This sermon is available in printed form in both Election Day Sermons (Covenant Foundation, 1996) and the excellent anthology by Ellis Sandoz, Political Sermons of the American Founding Era (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1998); it is accessible online at: http://consource.org/document/a-sermon-on-the-anniversary-of-the-independence-of-america-by-samuel-miller-1793-7-4/

It is also available as a photographic scan of an original copy, here.

Excerpts from Miller’s stirring conclusion are below to entice the reader to access the whole.

Again; if it be a solemn truth, that the prevalence of Christianity, has a natural and immediate tendency to promote political freedom, then, those are the truest and the wisest patriots, who study to increase its influence in society. Hence it becomes every American citizen to consider this as the great palladium of our liberty, demanding our first and highest care. . . .To each of you, then, my fellow citizens, on this anniversary of our independence, be the solemn address made! do you wish to stand fast in that liberty, wherewith the Governor of the universe hath made you free? Do you desire the increasing prosperity of your country? Do you wish to see the law respected-good order preserved, and universal peace to prevail? Are you convinced, that purity of morals is necessary for these important purposes? Do you believe, that the Christian religion is the firmest basis of morality? Fix its credit, then, by adopting it yourselves, and spread its glory by the luster of your example! And while you tell to your children, and to your children’s children, the wonderful works of the Lord, and the great deliverance which he hath wrought out for us, teach them to remember the Author of these blessings, and they will know how to estimate their value. Teach them to acknowledge the God of heaven as their King, and they will despise submission to earthly despots. Teach them to be Christians, and they will ever be free.

Dr. David W. Hall, Pastor

Midway Presbyterian Church

Powder Springs, Georgia

Rev.

Rev.  “A Long Obedience in the Same Direction”

“A Long Obedience in the Same Direction”