Sermon At A Service of Installation

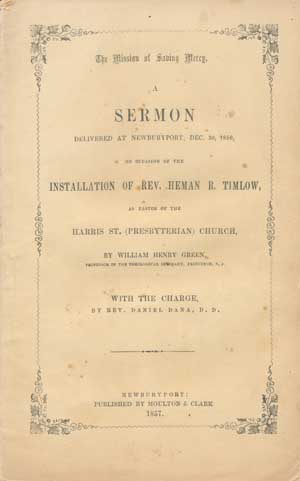

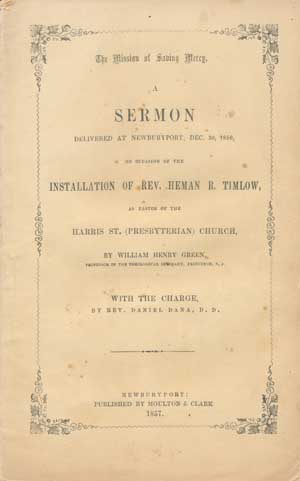

It was on this day, December 30th, in 1856, that the Rev. Dr. William Henry Green brought a sermon on the occasion of the installation of Rev. Heman R. Timlow, as pastor of the Harris Street Presbyterian Church, Newburyport, Massachusetts. Rev. Timlow had been called to serve this church following the resignation of the Rev. W.W. Eels in March the year prior. All of which is admittedly a rather obscure set of facts and we might honestly wonder why it should merit our attention?

It was on this day, December 30th, in 1856, that the Rev. Dr. William Henry Green brought a sermon on the occasion of the installation of Rev. Heman R. Timlow, as pastor of the Harris Street Presbyterian Church, Newburyport, Massachusetts. Rev. Timlow had been called to serve this church following the resignation of the Rev. W.W. Eels in March the year prior. All of which is admittedly a rather obscure set of facts and we might honestly wonder why it should merit our attention?

Among Presbyterians, the installation of a pastor remains to this day a service carried out in much the same way. So for one, if we were to look for a model for such an occasion, then here is one example. Moreover, we have here a sermon by an admittedly brilliant young man, at a point early in his remarkable career.

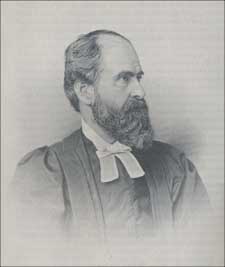

There is also the contrast of the youth of Dr. Green [1825-1900], just 31 years old when he served at the installation of this new pastor, compared with the advanced age of Rev. Dana, then near the end of his life yet still faithfully serving the Lord’s people at this installation. Dr. Green came from a long line of Presbyterians, among them, Jonathan Dickinson, first president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University). Green had graduated from Princeton Seminary in 1846, was ordained in 1848, and following a brief pastorate in Philadelphia, was installed in 1851 as professor of Biblical and Oriental Literature at the Princeton Theological Seminary. He remained a professor there until his death in 1900. Rev. Daniel Dana [1771-1859] as noted was near the end of his life, having long served the Presbyterian churches of Newburyport. It was Rev. Dana who had asked Dr. Green to bring the installation sermon on this occasion. Rev. Dana then brought the charge to the pastor. Others serving at this installation included the Rev. John Pike, of Rowley, who brought the charge to the people; and the Rev. A.G. Vermilye, of Newburyport, who extended the right hand of fellowship.

But the primary value of this sermon remains the message itself, as brought by Dr. Green that day. For his message, he chose the text of Luke 4: 18-19 :

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, to preach the acceptable year of the Lord.”

By the standards of that era, Green’s message is rather brief, taking up just 12-1/2 pages in print. Many of his peers would typically produce similar sermons of twenty pages or more. But length is no judge of quality, and Green is succinct for a purpose, and from a pastoral standpoint, could be seen as a hallmark of his long career at Princeton Seminary, indicative of the heart of his ministry.

The above text, as Dr. Green states in the opening of his sermon, contains an exposition of Christ’s earthly mission. It is the commission which He received from the Father and it is the reason why He was anointed with the Spirit above measure. It comprises the errand upon which He came into the world. And so, to give a glimpse of his sermon, here below are a few choice portions:—

“The mission of the Savior was to preach the Gospel to the poor, to heal the broken hearted, to preach deliverance to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, to preach the acceptable year of the Lord. And yet when He ascended to the Father, He left behind Him a world still unreconciled to God, still in its pollution, misery and sin. It was filled still with poor to whom no glad tidings had been carried, with captives whose prison doors were barred as tightly, whose fetters were as galling and whose miserable dungeons were as dark and cheerless as ever; with the broken hearted to whom no voice of the comforter had spoken relief, and with the blind whose sight was as far as ever from being removed. But judge not from this that His errand was was abortive and His work a failure.”

“The work of the world’s recovery was not one begun in a moment and ended in a moment. As there was a protracted period of preparation reaching through many ages and employing various and potent instrumentalities before He came; so there is needed a protracted period for that scheme which He set in operation and which He still conducts and superintends, to work out its expected and certain consummation. The whole might have been accomplished in an instant had the almighty grace of God so chosen; and the moment of Christ’s triumphant resurrection from the grave might have been signalized by the complete ingathering and perfect sanctification of all God’s elect people, by the utter overthrow of Satan’s baleful empire, and by the entire and final banishment from earth of sin and its accursed effects. And so, had God chosen, the world might have been created in a moment, and all its forms of beauty and its innumerable orders of creatures sprung instantaneously into being, instead of being gradually evolved through six successive days. But thus God did not work in creation; nor did He in redemption.”

“To what has been said it may be still further added, that the verses before us are descriptive of the mission of the church of God, as composed of those who have embraced this precious system of saving truth, and stand as its embodiment, its representatives and its champions before the world. . . .Every one who has received the gospel of God’s grace into his soul, is not only one redeemed from the power of the enemy, but one commissioned to ransom others; not only one upon whom the balm of Gilead has begun its work of cure; but a physician, a healer of the hurts and maladies of others; not only a captive loosed from bonds, but set to the work of breaking the chains of those who wear them still. Every Christian is not a mere passive recipient of the truth and of its saving benefits, but in his measure and according to his station, opportunity and ability, he is set for its defence and propagation. He is a light kindled that it may shine—salt put into the mass for the preservation of the whole. The gospel is given to the church of God to spread it and apply it everywhere. . . It is a work of solemn obligation; and to every Christian unemployed in this his bounden duty, comes his Savior’s reproving voice—’why stand ye all the day idle? go, work in my vineyard.’ “

Words to Live By:

The call of the Gospel is a call to real action here and now. Christ saved us that we might bear fruit—that we might live out the life of Christ, by the power of the Holy Spirit, and so be used of Him to draw others into His kingdom. For one, as Dr. Green is careful to point out elsewhere in his sermon,

“. . . there is no warrant for restricting the redeeming virtue of the gospel solely to what is spiritual and eternal, and excluding from the sphere of its potency that which is temporal; or rather since it is expressly declared, that godliness has the promise of the life that now is, as well as of that which is to come,—as the gospel is capable of undoing and was intended to undo all the mischiefs of the fall, and to banish suffering and sorrow from this present world as well as deliver from it in the next, the church is God’s grand engine of philanthropy. There is not a question bearing on man’s amelioration, individual, social or national, in which the church has not an interest, and in whose solution she should not take her share. There is not a cry of distress, that may be suffered to break upon her ear unregarded. She carries in her hand the potent remedy; and she may not, through her culpable inactivity or through her criminal lack of faith in its sovereign efficacy, keep back from suffering men, what Christ has charged her as His almoner with bestowing upon them. She must hold up the gospel which she has received, before the eyes of men, as God’s appointed cure for all the evils that are in the world. Nor may she content herself with the mere propounding of its abstract principles, nor with the diligent application of it to one class of man’s disorders; as though her caring for one part of her commanded work absolved her from the rest,—as though by caring for men’s eternal, she was absolved from all regard for their temporal interests,—as though after proffering eternal salvation to men, she was thenceforward discharged from further care for them, and might shut up her bowels of compassion from her suffering and needy brother. . . . She must not only hold up the gospel in one of its aspects, but hold it up in all,—not only state its principles but search out and exhibit its applications. ”

A print copy of the above sermon may be found preserved at the PCA Historical Center. Or more conveniently, it may be found on the Web by clicking here.

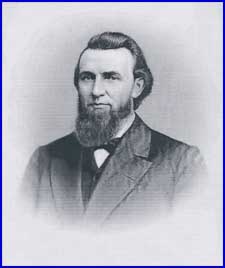

Henry Jackson Van Dyke, Sr., was born in Abington, Pennsylvania, 2 March 1822. He was educated at the University of Pennsylvania, graduating there in 1843 and later graduating from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1846. He was ordained by the Third Presbytery of Philadelphia in June of 1845 and installed as pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church at Bridgeton, New Jersey, where he served from 1845-1852. He was next called to pastor the First Presbyterian Church of Germantown, PA, but only served there briefly, 1852-1853. His his final and longest pastorate was at the First Presbyterian Church (Later renamed the Second Presbyterian Church, following a merger) of Brooklyn, New York, 1853-1891. He died in Brooklyn on 25 May 1891. Honors conferred during his life included the Doctor of Divinity degree, awarded by Westminster College of Fulton, Missouri, 1865. In 1876, he served as Moderator of the 88th General Assembly of the PCUSA, as it met in Brooklyn, NY, just seven years after the reunion of the Old School and New School divisions of that denomination. Rev. Van Dyke was survived by his wife, Henrietta Ashmead Van Dyke [1820-1893]. Their marriage produced two sons, Henry Jackson Van Dyke, Jr. [1852-1933], who later became a noted author and poet; and Paul Van Dyke [1859-1933]. Paul was a Presbyterian minister at Geneva, NY, 1887–89, and then taught church history at Princeton Theological Seminary, 1889–92.

Henry Jackson Van Dyke, Sr., was born in Abington, Pennsylvania, 2 March 1822. He was educated at the University of Pennsylvania, graduating there in 1843 and later graduating from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1846. He was ordained by the Third Presbytery of Philadelphia in June of 1845 and installed as pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church at Bridgeton, New Jersey, where he served from 1845-1852. He was next called to pastor the First Presbyterian Church of Germantown, PA, but only served there briefly, 1852-1853. His his final and longest pastorate was at the First Presbyterian Church (Later renamed the Second Presbyterian Church, following a merger) of Brooklyn, New York, 1853-1891. He died in Brooklyn on 25 May 1891. Honors conferred during his life included the Doctor of Divinity degree, awarded by Westminster College of Fulton, Missouri, 1865. In 1876, he served as Moderator of the 88th General Assembly of the PCUSA, as it met in Brooklyn, NY, just seven years after the reunion of the Old School and New School divisions of that denomination. Rev. Van Dyke was survived by his wife, Henrietta Ashmead Van Dyke [1820-1893]. Their marriage produced two sons, Henry Jackson Van Dyke, Jr. [1852-1933], who later became a noted author and poet; and Paul Van Dyke [1859-1933]. Paul was a Presbyterian minister at Geneva, NY, 1887–89, and then taught church history at Princeton Theological Seminary, 1889–92. By all means then you must also read the review written by James Renwick Willson Sloane [1823-1886], a Reformed Presbyterian pastor and contemporary of Rev. Van Dyke. See the link below, or again, visit the page listing Rev. Sloane’s works, at the Log College Press.

By all means then you must also read the review written by James Renwick Willson Sloane [1823-1886], a Reformed Presbyterian pastor and contemporary of Rev. Van Dyke. See the link below, or again, visit the page listing Rev. Sloane’s works, at the Log College Press.

It was on this day, December 30th, in 1856, that the Rev. Dr. William Henry Green brought a sermon on the occasion of the installation of Rev. Heman R. Timlow, as pastor of the Harris Street Presbyterian Church, Newburyport, Massachusetts. Rev. Timlow had been called to serve this church following the resignation of the Rev. W.W. Eels in March the year prior. All of which is admittedly a rather obscure set of facts and we might honestly wonder why it should merit our attention?

It was on this day, December 30th, in 1856, that the Rev. Dr. William Henry Green brought a sermon on the occasion of the installation of Rev. Heman R. Timlow, as pastor of the Harris Street Presbyterian Church, Newburyport, Massachusetts. Rev. Timlow had been called to serve this church following the resignation of the Rev. W.W. Eels in March the year prior. All of which is admittedly a rather obscure set of facts and we might honestly wonder why it should merit our attention?