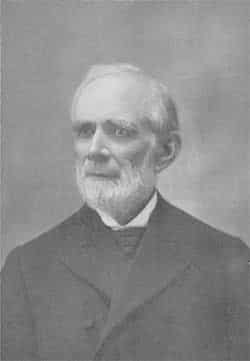

As is our habit, we present a sermon each Lord’s Day, and for today, we have a sermon titled “The Saving Christ.” This sermon is drawn from a slim volume entitled The Power of God unto Salvation, a book consisting of eight sermons preached in the chapel of the Theological Seminary at Princeton by the Rev. Dr. Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield, who served as professor at Princeton from 1887 until his death on this day, February 16th, in 1921.

While Dr. Warfield was a brilliant writer, known primarily for his theological and academic works, he is perhaps most accessible in his sermons. If you have put off reading anything by Warfield for fear it might be too difficult, please let me encourage you to take up this volume and read. I know you will find it rewarding:—

THE SAVING CHRIST.

“Faithful is the saying, and worthy of all acceptation, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners.”—1 Timothy 1:15 (Revised Version).

In these words we have the first of a short series of five “faithful sayings,” or current Christian commonplaces, incidentally adduced by the apostle Paul in the course of his letters to his helpers in the gospel—Timothy and Titus—i.e., in what we commonly call his Pastoral Epistles. They are a remarkable series of five “words,” and their appearance on the face of these New Testament writings is almost as remarkable as their contents.

Consider what the phenomenon is that is brought before us in these “faithful sayings.” Here is the apostle writing to his assistants in the proclamation of the gospel, little more than a third of a century, say, after the crucifixion of his Lord—scarcely thirty-three years after he had himself entered upon the great ministry that had been committed to him of preaching to the Gentiles the words of this life. Yet he is already able to remind them of the blessed contents of the gospel message in words that are the product of Christian experience in the hearts of the community. For just what these “faithful sayings” are, is a body of utterances in which the essence of the gospel has been crystallized by those who have tasted and seen its preciousness. Obviously the days when this gospel was brought as a novelty to their attention are past. The church has been founded, and in it throbs the pulses of a vigorous life. The gospel has been embraced and lived; it has been trusted and not found wanting; and the souls that have found its blessedness have had time to frame its precious turths into formulas. Formulas, I do not say, merely, that have passed from mouth to mouth, and been enshrined in memory after memory until they have become proverbs in the Christian community. Formulas rather, which have embedded themselves in the hearts of the whole congregation, have been beaten there into shape, as the deeper emotions of redeemed souls have played round them, and have emerged again suffused with the feelings which they have awakened and satisfied, and molded into that balanced and rhythmic form which is the hallmark of utterances that come really out of the living and throbbing hearts of the people.

If we were to judge of the spiritual attainments of the primitive Church solely by these specimens of its Christian thought, we should assuredly conceive exceedingly highly of them. Where can we go to find a truer or deeper insight into the heart of the gospel—a richer or fuller expression of all that the religious life at its highest turns upon? Certainly not to the apocryphal fragments of so-called “utterances of Jesus” raked out of the trash-heaps of some Oxyrhynchus or other. But just as truly not to the authentic remains of the early ages of the Church; which witness, indeed, to a living, vitalizing Christianity ordering all its life, but which distinctly reach to no such level of Christian thinking and feeling as these fragments point to. We are thus bidden to remember that in these five “sayings” we have, not the total product of the Christian thought of the age, perhaps not even a fair sample of it, but such items of it only as commended themselves to the mind and heart of a Paul, and rose joyously to his lips when he would fain exhort his fellows in the gospel to embrace and live by its essence. They come to us accordingly not merely as valuable fragments of the Christian thinking of the first period—of absorbing interest as they would be even from that point of view—but with the imprimatur of the apostle upon them as consonant with the mind of the Holy Spirit. They are dug from the mine of the Christian heart indeed, but they come to us stamped in the mintage of apostolic authority. The primitive Christian community it may have been that gave them form and substance, but it is the apostle who assures us that they are “faithful sayings, and worthy of all acceptation.”

And surely, when we come to look narrowly at the particular one of these “sayings” which we have chosen as our text, it is a great assertion that it brings us—an assertion which, if it be truly a “faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptation,” is well adapted to become even in this late and, it would fain believe itself, more instructed age, the watchword of the Christian Church and of every Christian heart. On the face of it, you will observe, it simply announces the purpose or, we may perhaps say, the philosophy, of the incarnation: “This is a faithfl saying, and worthy of all acceptation, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners.” But it announces the purpose of the incarnation in a manner that at once attracts attention. Even the very language in which it is expressed is startling, meeting us here in the midst of one of Paul’s letters. For this is not Pauling phraseology that stands before us here; as, indeed, it professes not to be—for does not Paul tell us that he is not speaking in his own person, but is adducing one of the jewels of the Church’s faith? At all events, it is the language of John that here confronts us, and whoever first cast the Church’s heart-conviction into this compressed sentence had assuredly learned in John’s school. For to John only belongs this phrase as applied to Christ: “He came into the world.” It is John only who preserves the Master’s declarations: “I came forth from the Father, and am come into the world”; “I am come a light into the world, that whosoever believeth on Me should not abide in darkness.” It is he only who, adopting, as is his wont, the very phraseology of his Master to express his own thought, tells us in his prologue that “the true Light—that lighteth every man—was coming into the world,” but though He was in the world, and the world was made by Him, yet the world knew Him not.

Hence emerges a useful hint for the interpretation of our passage. For in the Johannean phraseology which we have before us here—though certainly not in the Johannean phraseology only—the term “the world” does not express a purely local idea, but is suffused with a deep ethical significance. When we read accordingly of Christ Jesus coming into the “world,” we are not reading of a mere change of place on the part of our Lord—of a mere descent on His part from heaven to earth, as we may say. We are reading of the light coming into the darkness: “the world” is the sphere of darkness and shame and sin. It is, in a word, the great ethical contrast that is intended to be brought prominently before us, and in this lies the whole point of the incarnation as conceived by John, and as embodied in our passage. Jesus Christ, the Lord of glory, came into “the world”—into the realm of evil and the kingdom of sin. In our present passage this idea is enhanced by the sharp collocation with it of the term “sinners.” For, in the original, the word “sinners” stands next to the word “world,” with the effect of throwing the strongest possible emphasis on the ethical connotation. This is the faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptation, that the apostle commends to us—that “Christ Jesus came into the world, sinners to save.” What else, indeed, could He have come into “the world,” the sphere of evil, for—except to save sinners?

Surely, there meets us here a point that is worthy of our closest attention. We might have heard of Christ coming into the world, if the term could be taken in a merely local sense, with but a languid interest. But when we catch the ethical import of the term an explanation is at once demanded. What could such an one as Christ have to do in coming to such a place as the world? The incongruity of the thing requires accounting for. It is much as if we saw a fellow Christian in some compromising position. We might meet with him here, there, and elsewhere, and no remark be aroused. But by some change swing of the shutter as we pass by we see him standing in the midst of a drinking-saloon; we see him emerge from the door of a well-known gambling hell, or of some dreadful abode of shame. At once the need of an explanation rises within our puzzled minds, and the whole stress of the situation turns on the explanation. What was his purpose there? we anxiously inquire. So it is with Christ Jesus coming into the world; and so we feel in proportion as we realize the ethical contrariety suggested by the term. Thus it comes about that the primary emphasis of the passage is felt to rest on the account it gives of the situation it brings before us—on its explanation of how it happens that Christ Jesus could and did come into the world.

We despair of finding an English phraseology which will reproduce with exactitude the nice distribution of the stress. Suffice it to say that the strong emphasis falls on the fact that it was specifically to save sinners that Christ Jesus came, and that the way for this strength of emphasis is prepared by the use of phraseology which implies that there was no other conceivable end that He could have had in view in coming into such a place as the world except to deal with sinners, of which the world consists. He might indeed have come to judge the world; and in contrast with that the emphasis falls on the word “to save.” But He could not conceivably, being what He was, the Holy One and the Just, have come to such a place as the world is—the seat of shame and evil—save to deal with sinners. The essence of the whole declaration, therefore, is found in the joyful cry that it was specifically to save sinners that Christ Jesus came into this world of evil. And if that be true—simply true, broadly true, true just as it stands, and in all the reach of its meaning—why, then, from that alone we may learn what man is and what God is—what Christ Jesus is and His work in this world of ours—what hopes may illumine our darkness here below, and what joys shall be ours when this darkness passes away.

It would naturally be impossible for us to dip out all the fulness of such a great declaration in a half-hour’s meditation. It will be profitable for us, accordingly, to confine ourselves to bringing as clearly before us as may prove to be practicable two or three of its main implications. And may God the Holy Spirit help us to read it aright and to apply its lessons to our souls’ welfare!

First of all, then, let us observe that this “faithful saying” takes us back into the counsels of eternity and reveals to us the ground, in the decree of God, for the gift of His Son to the world, and the end sought to be obtained by His entrance into the likeness of sinful flesh. “Faithful is the saying,” says the apostle, “and worthy of all acceptation,” that Christ Jesus came into the world in order to save sinners.” That is to say, the occasion of the incarnation is rooted in sin, and the end of it is found in salvation from sin. And that is to say again, translating these facts into the terms of the decree, that the determination of God to send His Son and the determination of the Son to come into the world are grounded, in the counsel of God, on the contemplated fact of sin, and have as their design to provide a remedy for sin.

To continue reading this sermon by Dr. Warfield, click here, and continue reading from page 38.

To read more about the death of Dr. Warfield, click here.