While still new to the pastorate, and not yet thirty years old, it was on this day, April 12, 1797, that the the Rev. Samuel Miller delivered a discourse in New York City, before the Society for the Manumission of Slaves. [For those unfamiliar with the term, manumission is the act of freeing a slave.] Only an excerpt of this discourse, the fifth of Miller’s published works, is presented below, but a link has been provided in the title for those who would like to read the entire discourse. Would that Miller’s words had gripped early American society to conviction and action, to the eradication of evil! For one practical example of manumission in that same era, in which Reformed Presbyterians freed their slaves and at great personal cost, read chapter four of the Memoir of the Rev. Alexander McLeod.

While still new to the pastorate, and not yet thirty years old, it was on this day, April 12, 1797, that the the Rev. Samuel Miller delivered a discourse in New York City, before the Society for the Manumission of Slaves. [For those unfamiliar with the term, manumission is the act of freeing a slave.] Only an excerpt of this discourse, the fifth of Miller’s published works, is presented below, but a link has been provided in the title for those who would like to read the entire discourse. Would that Miller’s words had gripped early American society to conviction and action, to the eradication of evil! For one practical example of manumission in that same era, in which Reformed Presbyterians freed their slaves and at great personal cost, read chapter four of the Memoir of the Rev. Alexander McLeod.

Image : Pictured at right, the Rev. Dr. Samuel Miller, a portrait roughly contemporaneous with the time of the following discourse.

Words to Live By: Remember this!—Individuals and nations are alike in this, that sin is not easily rooted out. Once it takes hold, it can be a most difficult thing to remove it, and like old injuries, the scars that remain constantly remind us of our sin. Far better to stop sin at its first rising, before it takes root.

A Discourse, delivered April 12, 1797, at the Request of and Before the New-York Society

for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and Protecting such of them as have been or may be Liberated.

by Samuel Miller, A.M., one of the ministers of the United Presbyterian churches

in the city of New-York, and Member of said Society.

New-York: Printed by T. and J. Swords, No. 99 Pearl-street, 1797.

. . . That, in the close of the eighteenth century, it should be esteemed proper and necessary, in any civilized country, to institute discourses to oppose the slavery and commerce of the human species, is a wonderful [i.e., a thing to be wondered at] fact in the annals of society! But that this country should be America, is a solecism only to be accounted for by the general inconsistency of the human character. But, after all, the surprise that Patriotism can feel, and all the indignation that Morality can suggest on this subject, the humiliating tale must be told—that in this free country—in this country, the plains of which are still stained with blood shed in the cause of liberty,—in this country, from which has been proclaimed to distant lands, as the basis of all our political existence, the noble principle, that “ALL MEN ARE BORN FREE AND EQUAL,”—in this country there are slaves!—men are bought and sold! Strange, indeed! that the bosom which glows at the name of liberty in general, and the arm which has been so vigorously exerted in vindication of human rights, should yet be found leagued on the side of oppression, and opposing their avowed principles!

Much, indeed, has been done by many benevolent individuals and societies, to abolish this disgraceful practice, and to improve the condition of those unhappy people, whom the ignorance or the avarice of our ancestors has bequeathed to us as slaves. Still, however, notwithstanding all the labours and eloquence which have been directed against it, the evil continues; still laws and practices exist, which loudly call for reform; still MORE THAN HALF A MILLION of our fellow creatures in the United States are deprived of that which, next to life, is the dearest birth-right of man.

To deliver the plain dictates of humanity, justice, religion, and good policy, on this subject, is the design of the present discourse. In doing this, it will not be expected that any thing new should be offered. It is not a new subject; and every point of view in which it can be considered has been long since rendered familiar by the ingenious and the humane. All that is left for me is, to bring to your remembrance principles which, however well known, cannot be too often repeated; and to exhibit some of the most obvious arguments against an evil which, though generally acknowledged, is still practically persisted in.

And here I shall pass over in silence the unnumbered cruelties, and the violations of every natural and social tie, which mark the African trade, and which attend the injured captives in dragging them from their native shores, and from all the attachments of life. I shall not call you to contemplate the miseries and hardships which follow them into servitude, and render their life a cup of unmingled bitterness. Unwilling to wound your feelings, or my own, by the melancholy recital, over these scenes I would willingly draw a veil; and confine myself to principles and views of the subject more immediately applicable to ourselves.

That enslaving, or continuing to hold in slavery, those who have forfeited their liberty by no crime, is contrary to the dictates both of justice and humanity, I trust few who hear me will be disposed to deny. However the judgment of some may be biassed by the supposed peculiarity of certain cases, I presume that with regard to the abstract principle, there can be but one opinion among enlightened and candid minds. What is the end of all social connection but the advancement of human happiness? And what can be a more plain and indisputable principle of republican government, than that all the right which society possesses over individuals, or one man over another, must be founded either upon contract, express or implied, or upon forfeiture by crime? But, are the Africans and their descendants enslaved upon either of these principles? Have they voluntarily surrendered their liberty to their whiter brethren? or have they forfeited their natural right to it by the violation of any law? Neither of these is pretended by the most zealous advocates for slavery. By what ties, then, are they held in servitude? By the ties of force and injustice only; by ties which are equally opposed to the reason of things, and to the fundamental principles of all legitimate association.

In the present age and country, none, I presume, will rest a defence of slavery on the ground of superior force; the right of captivity; or any similar principle, which the ignorance and the ferocity of ancient times admitted as a justifiable tenure of property. It is to be hoped the time is passed, never more to return, when men would recognize maxims as subversive of morality as they are of social happiness. Can the laws and rights of war be properly drawn into precedent for the imitation of sober and regular government? Can we sanction the detestable idea, that liberty is only an advantage gained by strength, and not a right derived from nature’s God. Such sentiments become the abodes of demons, rather than societies of civilized men.

Pride, indeed, may contend, that these unhappy subjects of our oppression are aninferior race of beings; and are therefore assigned by the strictest justice to a depressed and servile station in society. But in what does this inferiority consist? In a difference of complexion and figure? Let the narrow and illiberal mind, who can advance such an argument, recollect whither it will carry him. In traversing the various regions of the earth, from the Equator to the Pole, we find an infinite diversity of shades in the complexion of men, from the darkest to the fairest hues. If, then, the proper station of the African is that of servitude and depression, we must also contend, that every Portuguese and Spaniard is, though in a less degree, inferior to us, and should be subject to a measure of the same degradation. Nay, if the tints of colour be considered the test of human dignity, we may justly assume a haughty superiority over our southern brethren of this continent, and devise their subjugation. In short, upon this principle, where shall liberty end? or where shall slavery begin? At what grade is it that the ties of blood are to cease? And how many shades must we descend still lower in the scale, before mercy is to vanish with them?

But, perhaps, it will be suggested, that the Africans and their descendants are inferior to their whiter brethren in intellectual capacity, if not in complexion and figure. This is strongly asserted, but upon what ground? Because we do not see men who labour under every disadvantage, and who have every opening faculty blasted and destroyed by their depressed condition, signalize themselves as philosophers? Because we do not find men who are almost entirely cut off from every source of mental improvement, rising to literary honours? To suppose the Africans of an inferior radical character, because they have not thus distinguished themselves, is just as rational as to suppose every private citizen of an inferior species, who has not raised himself to the condition of royalty. But, the truth is, many of the negroes discover great ingenuity, notwithstanding their circumstances are so depressed, and so unfavourable to all cultivation. They become excellent mechanics and practical musicians, and, indeed, learn every thing their masters take the pains to teach them.* And how far they might improve in this respect, were the same advantages conferred on them that freemen enjoy, is impossible for us to decide until the experiment be made.

[*Having been, for two years, a monthly visitor of the African School in this city, I directed particular attention to the capacity and behaviour of the scholars, with a view to satisfy myself on the point in question. And, to me, the negro children of that institution appeared, in general, quite as orderly, and quite as ready to learn, as white children.]

Aristotle long ago said—“Men of little genius, and great bodily strength, are by nature destined to serve, and those of a better capacity to command. The natives of Greece, and of some other countries, being naturally superior in genius, have a natural right to empire; and the rest of mankind, being naturally stupid, are destined to labour and slavery.”* [*De Republica, book 1, chap. 5, 6.] What would this great philosopher have thought of his own reasoning, had he lived till the present day? On the one hand, he would have seen his countrymen, of whose genius he boasts so much, lose with their liberty all mental character; while, on the other, he would have seen many nations, whom he consigned to everlasting stupidity, show themselves equal in intellectual power to the most exalted of human kind.

Again—Avarice may clamorously contend, that the laws of property justify slavery; and that every one has an undoubted right to whatever has been obtained by fair purchase or regular descent. To this demand the answer is plain. The right which every man has to his personal liberty is paramount to all the laws of property. The right which every one has to himself infinitely transcends all other human tenures. Of consequence, the latter can never be set in opposition to the former. I do not mean, at present, to decide the question, whether the possessors of slaves, when called upon by public authority to manumit them, should be indemnified for the loss they sustain. This is a separate question, and must be decided by a different tribunal from that before which I bring the general subject. All I contend for at present is, that no claims of property can ever justly interfere with, or be suffered to impede the operation of that noble and eternal principle, that “all men are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights—and that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

These principles and remarks would doubtless appear self-evident to all, were the case of the unhappy Africans for a moment made our own. Were it made a question, whether justice permitted the sable race of Guinea to carry us away captive from our own country, and from all its tender attachments, to their own land, and there enslave us and our posterity for ever;—were it made a question, I say, whether all this would be consistent with justice and humanity, one universal and clamorous negative would show how abhorrent the principle is from our minds, when not blinded by prejudice. Tell us, ye who were lately pining in ALGERINE BONDAGE! [i.e., enslavement in Algeria. For several centuries Algeria was the primary base of the Barbary pirates]. Tell us whether all the wretched sophistry of pride, or of avarice, could ever reconcile you to the chains of barbarians, or convince you that man had a right to oppress and injure man? Tell us what were your feelings, when you heard the pityless tyrant, who had taken or bought you, plead either of these rights for your detention; and justify himself by the specious pretences of capture or of purchase, in riveting your chains?

. . . But higher laws than those of common justice and humanity may be urged against slavery. I mean THE LAWS OF GOD, revealed in the Scriptures of truth. This divine system, in which we profess to believe and to glory, teaches us, that God has made of one blood all nations of men that dwell on the face of the whole earth. It teaches us, that, of whatever kindred or people, we are all children of the same common Father; dependent on the same mighty power; and candidates for the same glorious immortality. It teaches us, that we should do to all men whatever we, in like circumstances, would that they should do unto us. It teaches us, in a word, that love to man, and a constant pursuit of human happiness, is the sum of all social duty.—Principles these, which wage eternal war both with political and domestic slavery—Principles which forbid every species of domination, excepting that which is founded on consent, or which the welfare of society requires.

[Dr. Miller’s discourse continues on at some length. To read the rest of it, please follow the link embedded in the title at the top of the page.]

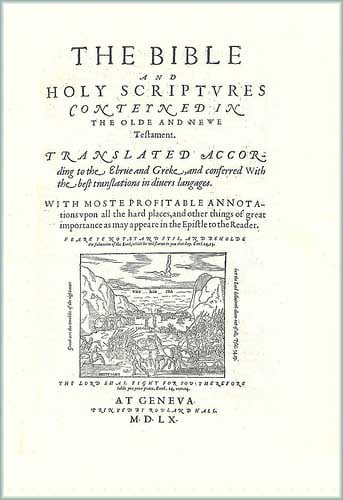

It was said that in most colonial homes in America, Presbyterians owned at least several books for use by and for their families. The first one was, of course, the Bible. And contrary to many expectations, that Bible version was not the King James Version, but rather the Genevan Bible. Remember, the King James version was introduced because of the Reformed foot notes of the Genevan Bible. That introduction was marked by mistakes, such as the inclusion of the Apocrypha into the first edition of the King James Version. It was left out in the second edition, and indeed, to cause people to buy it, the printer of the version placed on the flyleaf “Authorized Version.” All these caused the many Presbyterian and Reformed Christians to bring the Genevan edition to the shores of America.

It was said that in most colonial homes in America, Presbyterians owned at least several books for use by and for their families. The first one was, of course, the Bible. And contrary to many expectations, that Bible version was not the King James Version, but rather the Genevan Bible. Remember, the King James version was introduced because of the Reformed foot notes of the Genevan Bible. That introduction was marked by mistakes, such as the inclusion of the Apocrypha into the first edition of the King James Version. It was left out in the second edition, and indeed, to cause people to buy it, the printer of the version placed on the flyleaf “Authorized Version.” All these caused the many Presbyterian and Reformed Christians to bring the Genevan edition to the shores of America.

While still new to the pastorate, and not yet thirty years old, it was on this day, April 12, 1797, that the the Rev. Samuel Miller delivered a discourse in New York City, before the Society for the Manumission of Slaves. [For those unfamiliar with the term, manumission is the act of freeing a slave.] Only an excerpt of this discourse, the fifth of Miller’s published works, is presented below, but a link has been provided in the title for those who would like to read the entire discourse. Would that Miller’s words had gripped early American society to conviction and action, to the eradication of evil! For one practical example of manumission in that same era, in which Reformed Presbyterians freed their slaves and at great personal cost, read

While still new to the pastorate, and not yet thirty years old, it was on this day, April 12, 1797, that the the Rev. Samuel Miller delivered a discourse in New York City, before the Society for the Manumission of Slaves. [For those unfamiliar with the term, manumission is the act of freeing a slave.] Only an excerpt of this discourse, the fifth of Miller’s published works, is presented below, but a link has been provided in the title for those who would like to read the entire discourse. Would that Miller’s words had gripped early American society to conviction and action, to the eradication of evil! For one practical example of manumission in that same era, in which Reformed Presbyterians freed their slaves and at great personal cost, read

Dr. J. Gresham Machen was the recognized leader of the conservatives in the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A. Founder and president of Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he was still a member minister of the New Brunswick, New Jersey Presbytery, though he had tried unsuccessfully to transfer to the Philadelphia Presbytery. Against him was Dr. Robert Speer, present head of the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A.

Dr. J. Gresham Machen was the recognized leader of the conservatives in the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A. Founder and president of Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he was still a member minister of the New Brunswick, New Jersey Presbytery, though he had tried unsuccessfully to transfer to the Philadelphia Presbytery. Against him was Dr. Robert Speer, present head of the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A.