A Yankee Chaplain In the Union Army

by Rev. David T Myers

My favorite story about the military chaplaincy was that of an unnamed Union chaplain who must have been tired of marching with his troops. So upon entering the Confederate states, he stole the first horse he found on a farm. The Southern farmer, upset about the loss of his horse, complained to the Union Colonel. The latter ordered the chaplain to explain himself about this horse. He answered by saying that Jesus Christ had borrowed a donkey to go to Jerusalem! Whereupon the Colonel made four short points back to the chaplain. One, he wasn’t Jesus Christ. Two, a donkey is not a horse. Three, the regiment was going to Richmond, not Jerusalem. And last, the sooner he returned the horse, the better it would be for him. The horse was returned in short order.

My favorite story about the military chaplaincy was that of an unnamed Union chaplain who must have been tired of marching with his troops. So upon entering the Confederate states, he stole the first horse he found on a farm. The Southern farmer, upset about the loss of his horse, complained to the Union Colonel. The latter ordered the chaplain to explain himself about this horse. He answered by saying that Jesus Christ had borrowed a donkey to go to Jerusalem! Whereupon the Colonel made four short points back to the chaplain. One, he wasn’t Jesus Christ. Two, a donkey is not a horse. Three, the regiment was going to Richmond, not Jerusalem. And last, the sooner he returned the horse, the better it would be for him. The horse was returned in short order.

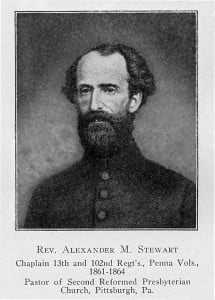

Our post today deals with a Yankee chaplain who was considerably more righteous than the one in our first paragraph. Alexander Morrison Stewart, of whom we have posted before on February 24 in 2013 regarding his civilian ministry in five Presbyterian churches, joined the 13th Pa. Volunteer Regiment (designated in the middle of that civil war as the 102nd Pa. Volunteer Regiment) with a letter to its commander on April 15, 1861. The letter read:

Dear Sir: As it is the praiseworthy custom of Christian countries to afford their soldiers during military service the means and consolations of religions, I therefore offer myself. The present war is in many of its aspects a religious one. It is a battle for truth and righteousness, for liberty against despotism. Of these things, our soldiers should be constantly reminded. My proposed service is, by the grace of God, to make of those under your command better men and hence better soldiers; to comfort the sick and wounded, and to console the dying; and yet if a strait comes, and you would require of me to wield the sword or handle the rifle, I would have no hesitancy.”

The Rev. Stewart was received into the regiment as a Protestant chaplain, and served the entire time with the 102nd Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment. As an aside, he was commissioned to send regular columns back to his hometown paper in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, telling of his experiences. Later, in 1865, these columns were published into a book titled Camp, March and Battle-field; or, Three years and a Half with the Army of the Potomac, which can be found here.

One of his reports was descriptive of the first prayer meeting in camp. He wrote “At the close of public worship last, intimation was given, that a prayer meeting would beheld in the tent at eight o’clock that same evening. (Despite rain at the appointed hour) the tent was completely jammed. Some of the officers readily took part in the exercises. It was a most refreshing as well as an encouraging meeting; an indication that much is to e hoped for in time from this our Bethel in camp.”

Words to Live By:

There are still godly and faithful chaplains in our nation’s military services. Each of our Presbyterian and Reformed churches should adopt a military chaplain, to pray for, encourage, and help in any way for him to fulfill God’s ministry among the troops. Pray for wisdom in this day of political correctness to stand up for truth and righteousness. Contact the Presbyterian and Reformed Chaplaincy of the Ministry to North America, found on line, to find out how you can support those on the front lines of the gospel in the military.

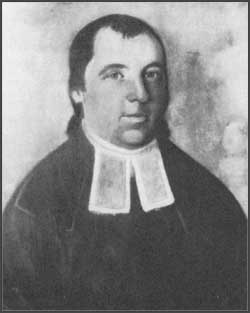

James Muir was a son of the Rev. Dr. George and Tibbie (Wardlaw) Muir, and he was born on the 12th of April, 1757, in Cumnock, Scotland. Both his father and grandfather were highly respected ministers in the Church of Scotland, and the town of Cumnock was where his father served as pastor.

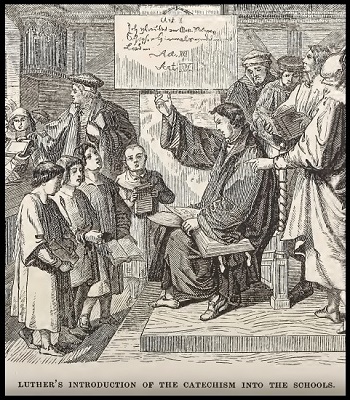

James Muir was a son of the Rev. Dr. George and Tibbie (Wardlaw) Muir, and he was born on the 12th of April, 1757, in Cumnock, Scotland. Both his father and grandfather were highly respected ministers in the Church of Scotland, and the town of Cumnock was where his father served as pastor. nd for those with some knowledge of the literature of the Reformation might be Martin Luther’s The Bondage of the Will, his translation of the Bible into German, or his work on the New Testament book of Galatians. In the case of John Calvin one might think of Institutes of the Christian Religion, which was published in several editions and languages, or possibly his commentaries on many of the books of Scripture would come to mind. These works by both Luther and Calvin were written primarily for ministers, teachers, and those involved in the debates about doctrine in their era, but one of the most influential types of publications for reform was the catechism. The word “catechism” comes from the Greek language and it describes a text used for oral instruction which most often followed a question and answer format to teach essentials. In conjunction with Bibles translated into the common languages of the nations, catechisms were used to train believers in the fundamentals of faith, salvation, and Christian living. In the picture accompanying this article, Martin Luther is teaching his catechism to children in a classroom to provide them with doctrinal instruction.

nd for those with some knowledge of the literature of the Reformation might be Martin Luther’s The Bondage of the Will, his translation of the Bible into German, or his work on the New Testament book of Galatians. In the case of John Calvin one might think of Institutes of the Christian Religion, which was published in several editions and languages, or possibly his commentaries on many of the books of Scripture would come to mind. These works by both Luther and Calvin were written primarily for ministers, teachers, and those involved in the debates about doctrine in their era, but one of the most influential types of publications for reform was the catechism. The word “catechism” comes from the Greek language and it describes a text used for oral instruction which most often followed a question and answer format to teach essentials. In conjunction with Bibles translated into the common languages of the nations, catechisms were used to train believers in the fundamentals of faith, salvation, and Christian living. In the picture accompanying this article, Martin Luther is teaching his catechism to children in a classroom to provide them with doctrinal instruction.