Our second guest author this week is Barry Waugh, with a post drawn from his own blog, Presbyterians of the Past. Barry’s blog posts tend to be fuller treatments of a subject than what we typically have time to provide here, and so you would do well to add his blog to your reading schedule. What follows is a shorter version of his recent post on Patrick of Ireland. Click here to read the full post.

PATRICK OF IRELAND, 390-461

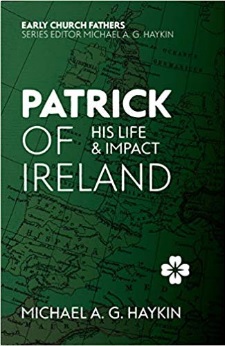

The next Lord’s Day will occur on March 17, which is the calendar date remembered as St. Patrick’s Day. While the Sabbath is being kept holy by some, the day named for Patrick will likely be celebrated with revelry and little if any concern for Patrick or his ministry. There are only two extant writings by him Confession and Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus. The first work is an autobiographic defense of his integrity as a minister in the face of accusations to the contrary; the second writing rebukes a military commander named Coroticus for kidnapping and killing Christians. These two works provide a more accurate picture of Patrick than do the myths about him and miracles attributed to him. Michael A. G. Haykin’s Patrick of Ireland: His Life & Impact points out that the real Patrick is more interesting than the one created over the centuries by tales and fables. When one reads Confession, it is obvious that Patrick had a command of Scripture and used it to teach the Irish about the Triune God and the gracious atonement accomplished by the Son. Patrick’s emphases on theology proper and Christology are indicative of the difficulties faced by missionaries as they communicated one God in three persons and Christ the God-man to pagans worshipping numerous individual gods. The authenticity is debated, as with much information about Patrick, but it is said he used clover with its three leaves united in one sprig to illustrate the three persons of the Trinity united in one God. As with any illustration of the Trinity, it breaks down at one point or another, but it likely worked well for Patrick’s purpose as he taught the grace of Christ.

The next Lord’s Day will occur on March 17, which is the calendar date remembered as St. Patrick’s Day. While the Sabbath is being kept holy by some, the day named for Patrick will likely be celebrated with revelry and little if any concern for Patrick or his ministry. There are only two extant writings by him Confession and Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus. The first work is an autobiographic defense of his integrity as a minister in the face of accusations to the contrary; the second writing rebukes a military commander named Coroticus for kidnapping and killing Christians. These two works provide a more accurate picture of Patrick than do the myths about him and miracles attributed to him. Michael A. G. Haykin’s Patrick of Ireland: His Life & Impact points out that the real Patrick is more interesting than the one created over the centuries by tales and fables. When one reads Confession, it is obvious that Patrick had a command of Scripture and used it to teach the Irish about the Triune God and the gracious atonement accomplished by the Son. Patrick’s emphases on theology proper and Christology are indicative of the difficulties faced by missionaries as they communicated one God in three persons and Christ the God-man to pagans worshipping numerous individual gods. The authenticity is debated, as with much information about Patrick, but it is said he used clover with its three leaves united in one sprig to illustrate the three persons of the Trinity united in one God. As with any illustration of the Trinity, it breaks down at one point or another, but it likely worked well for Patrick’s purpose as he taught the grace of Christ.

Patrick was born in Banavem Taberniæ the son of Calpurnius, who was the son of Potitus. Calpurnius was a public official and a “deacon” (diaconum), and Patrick’s grandfather was a “presbyter” (presbyteri, translated also “priest” or “elder”). Haykin notes that the precise location of his birthplace is unknown, but it is believed to be somewhere along the west coast of England or possibly Scotland. Regardless of his place of birth, Patrick grew up in the church, but the message of Christ fell on ears that were not yet ears to hear. He lived with his Roman-British family until the age of sixteen when he was abducted and enslaved in the land that came to be named Ireland. At the time, the Romans called the island Hibernia or Scotia. Patrick shepherded sheep as a physical slave but was released from slavery to sin by faith in Christ through the ministry of local Christians. While watching flocks he prayed nearly without ceasing and found the Psalms beneficial for petitioning and praising God. Patrick had something in common with another shepherd, King David. After about six years, Patrick managed to escape his captors, made his way to a ship, and left Ireland. . .

. . . Michael Haykin makes the case that Patrick was presbyterian. Note the lower case “p.” He was presbyterian in that he believed in rule by elders. Some Presbyterians of the past agree with Haykin’s perspective, such as Thomas Smyth (1808-1873). Smyth was the minister of Second Presbyterian Church, Charleston, South Carolina for a number of years and was of Irish descent. His father was a Presbyterian elder. Smyth presents his case for Patrick’s presbyterianism in Presbytery and Not Prelacy the Scriptural and Primitive Polity in vol. 2 of the Complete Works of Rev. Thomas Smyth, D.D. Smyth examined the Scripture passages relevant to polity and moved on to contend historically that the Irish were first converted by the missionary efforts of eastern Christianity and not western. The missionaries were associates or disciples of the Apostle John who believed in rule by elders as taught in Acts and the pastoral epistles. Even though Smyth uses the word prelacy in the title of his book, his concern is not only episcopal government as manifest in the Church of Ireland or of England, but also Roman Catholicism. See the section beginning on page 460 titled, “The Primitive Churches in Ireland were Presbyterian,” where Smyth argues for presbyterian government against episcopal and then presents his case for Patrick the presbyterian. But there was another perspective on the polity of the ancient church in Ireland which came from James Ussher two-hundred years earlier. Theologically, Ussher [who is pictured above left] and Smyth would have agreed on a great amount of doctrine because Ussher’s Irish Articles, 1615, and his Body of Divinity provided abundant content for the Westminster Standards. There are portions of the Shorter Catechism in particular that appear to have been lifted from Body (see explanatory note below). But the two Irishmen did not approach their homeland’s polity history from the same perspective. Ussher was Archbishop of Armagh, the bishop of the Church of Ireland. As Smyth made his case that Patrick and Ireland were originally presbyterian, so Ussher defended the nation’s episcopal origins in A Discourse of the Religion Anciently Professed by the Irish and British (Works 4:235ff). Ussher, as Smyth, directs his polemics against the papacy, but then he defends episcopal government for the Irish church. His Discourse goes beyond an apologetic for episcopacy to interact with key doctrinal differences with Catholicism. Ussher and Smyth could agree that Patrick was not Catholic, but debates concerning whether he was presbyterian, episcopal, or Catholic will likely continue. Hopefully, these questions of church government will not interfere with gaining appreciation for an interesting and dedicated servant of God named Patrick.

. . . Michael Haykin makes the case that Patrick was presbyterian. Note the lower case “p.” He was presbyterian in that he believed in rule by elders. Some Presbyterians of the past agree with Haykin’s perspective, such as Thomas Smyth (1808-1873). Smyth was the minister of Second Presbyterian Church, Charleston, South Carolina for a number of years and was of Irish descent. His father was a Presbyterian elder. Smyth presents his case for Patrick’s presbyterianism in Presbytery and Not Prelacy the Scriptural and Primitive Polity in vol. 2 of the Complete Works of Rev. Thomas Smyth, D.D. Smyth examined the Scripture passages relevant to polity and moved on to contend historically that the Irish were first converted by the missionary efforts of eastern Christianity and not western. The missionaries were associates or disciples of the Apostle John who believed in rule by elders as taught in Acts and the pastoral epistles. Even though Smyth uses the word prelacy in the title of his book, his concern is not only episcopal government as manifest in the Church of Ireland or of England, but also Roman Catholicism. See the section beginning on page 460 titled, “The Primitive Churches in Ireland were Presbyterian,” where Smyth argues for presbyterian government against episcopal and then presents his case for Patrick the presbyterian. But there was another perspective on the polity of the ancient church in Ireland which came from James Ussher two-hundred years earlier. Theologically, Ussher [who is pictured above left] and Smyth would have agreed on a great amount of doctrine because Ussher’s Irish Articles, 1615, and his Body of Divinity provided abundant content for the Westminster Standards. There are portions of the Shorter Catechism in particular that appear to have been lifted from Body (see explanatory note below). But the two Irishmen did not approach their homeland’s polity history from the same perspective. Ussher was Archbishop of Armagh, the bishop of the Church of Ireland. As Smyth made his case that Patrick and Ireland were originally presbyterian, so Ussher defended the nation’s episcopal origins in A Discourse of the Religion Anciently Professed by the Irish and British (Works 4:235ff). Ussher, as Smyth, directs his polemics against the papacy, but then he defends episcopal government for the Irish church. His Discourse goes beyond an apologetic for episcopacy to interact with key doctrinal differences with Catholicism. Ussher and Smyth could agree that Patrick was not Catholic, but debates concerning whether he was presbyterian, episcopal, or Catholic will likely continue. Hopefully, these questions of church government will not interfere with gaining appreciation for an interesting and dedicated servant of God named Patrick.

Words to Live By:

It is good to think of Patrick of Ireland and his contribution to the history of the church, but he should not be remembered with the common “carousing and drunkenness” associated with March 17. Instead, “the Lord Jesus Christ” should be put on in faith with “no provision for the flesh in regard to its lusts.” These words from Romans 13:13, 14 confronted Patrick’s contemporary, Bishop Augustine, with his own sin when he responded to Christ in faith. Patrick of Ireland would call the people of Irish heritage and all others to worship the Triune God through faith in Christ on this Lord’s Day.

BARRY WAUGH

Notes— Michael A. G. Haykin’s book is Patrick of Ireland: His Life & Impact, 2014, published by Christian Focus, Fern, Ross-shire, Scotland, which is a selection in the publisher’s Early Church Fathers Series. Other books in this series are edited by Professor Haykin and include Basil of Caesarea, Cyprian of Carthage, and Hilary of Poitiers. Based on my reading of the Patrick book, I would think the other selections in the series would be fine introductions to the church fathers. Present day Christians may be acquainted with Augustine because of his Confessions, but generally speaking, knowledge of the ancient fathers of the church is limited. However, reading books from the Early Church Fathers Series would improve the situation.

If interested in the life of an Irishman who was a Presbyterian then read on this site the biography of Thomas Witherow (1824-1890).

The map section is from the nicely done map located on Wikimedia titled, “The Roman Empire About 395.”

Regarding Ussher’s Body of Divinity, some contend that Ussher did not write it, after all he is not on the title page as author. It was published in London in 1645 which was an opportune location and date for the Westminster Asssembly’s deliberations in the Jerusalem Chamber. Body of Divinity would have been available for composition of the Shorter Catechism which was approved August 22, 1648 (see: Chad VanDixhoorn’s Minutes and Papers of the Westminster Assembly, 4:780). Ussher was invited to the Assembly, but it is believed he did not attend. However, did he manouver his Body into the Jerusalem Chamber instead? Ussher was likely sympathetic to what the divines wanted to accomplish doctrinally, but he could not physically be present as Archbishop of Ireland under the authority of the Church of England. In 1645, the Civil War was going poorly for King Charles I and his supporters, but there was always the odd chance he could maintain his rule. If Ussher had attended the Assembly he would have done so with considerable potential personal risk.

The Latin edition used for this article is Libri Sancti Patricii, number 4 in the series, Texts for Students, ed. Newport J. D. White and published in London by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1918 (title page pictured above); the English version was translated by White and is titled, St. Patrick, His Writings and Life, which is in the series Translations of Christian Literature, Series V, Lives of the Celtic Saints, and it too was published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, 1920.

John Skinner’s translations are in The Confession of Saint Patrick, New York: Doubleday, 1998, and David Howlett’s book is titled, The Book of Letters of Saint Patrick the Bishop, published in Dublin by Four Courts Press, 1994.