Take Care How You Stand Against Error.

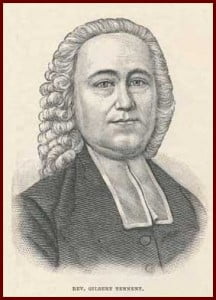

The following letter requires some introduction and explanation. The Rev. Gilbert Tennent was a prominent Presbyterian in the middle of the eighteenth-century. He took a strong stand against formalism and what is often termed “dead orthodoxy.” Gilbert Tennent had become one of the leading lights in what historians now call the Great Awakening. He favored the practice of revivals, but was opposed by some among the Presbyterians in the colonies. Eventually there was a division in the still rather young Presbyterian denomination, a division between the Old Side and the New Side, with Tennent one of the leaders of the New Side faction. But no sooner had this split occurred, than Rev. Tennent began to regret the division. For one, there were other, greater errors afoot.

Milton Coalter, in his book, Gilbert Tennent: Son of Thunder, explains:

Tennent was convinced that the Moravian system represented the greatest challenge to the Awakening’s integrity to date because it threatened to capsize the revival’s previous balance between a fervent experimental piety and sober theological reflection. But many Awakening supporters did not see these dangers in the Moravians’ theology. Indeed, they regarded the Unitas Fratrum as the truest expression of the movement.

The growing success enjoyed by Zinzendorf’s followers in attracting revival converts soon threw Tennent into a period of soul searching. The Awakening leader began to ask himself if the movement he had promoted was not the spur to doctrinal error and emotional enthusiasm that his opponents had claimed it to be from the start. Tennent expressed his inner turmoil over this question in a letter to Jonathan Dickinson during February 1742:

“February 12, 1742.

“I have many afflicting thoughts about the debates which have subsisted in our synod for some time. I would to God the breach were healed, were it the will of the Almighty. As for my own part, wherein I have mismanaged in doing what I did, I do look upon it to be my duty, and should be willing to acknowledge it in the openest manner. I cannot justify the excessive heat of temper which has sometime appeared in my conduct. I have been of late, since I returned from New England, visited with much spiritual desertion and distresses of various kinds, coming in a thick and almost continual succession, which have given me a greater discovery of myself than I think I ever had before. These things, with the trial[2] of the Moravians, have given me a clear view of the danger of every thing which tends to enthusiasm and division in the visible church. I think that while the enthusiastical Moravians, and Long-beards or Pietists, are uniting their bodies, (no doubt to increase their strength and render themselves more considerable,) it is a shame that the ministers who are in the main of sound principles in religion should be divided and quarrelling. Alas for it! my soul is sick for these things. I wish that some scriptural methods could be fallen upon to put an end to these confusions. Some time since I felt a disposition to fall on my knees, if I had opportunity, to entreat them to be at peace.

“I have many afflicting thoughts about the debates which have subsisted in our synod for some time. I would to God the breach were healed, were it the will of the Almighty. As for my own part, wherein I have mismanaged in doing what I did, I do look upon it to be my duty, and should be willing to acknowledge it in the openest manner. I cannot justify the excessive heat of temper which has sometime appeared in my conduct. I have been of late, since I returned from New England, visited with much spiritual desertion and distresses of various kinds, coming in a thick and almost continual succession, which have given me a greater discovery of myself than I think I ever had before. These things, with the trial[2] of the Moravians, have given me a clear view of the danger of every thing which tends to enthusiasm and division in the visible church. I think that while the enthusiastical Moravians, and Long-beards or Pietists, are uniting their bodies, (no doubt to increase their strength and render themselves more considerable,) it is a shame that the ministers who are in the main of sound principles in religion should be divided and quarrelling. Alas for it! my soul is sick for these things. I wish that some scriptural methods could be fallen upon to put an end to these confusions. Some time since I felt a disposition to fall on my knees, if I had opportunity, to entreat them to be at peace.

“I remain, with all due honour and respect, your poor worthless brother in the ministry.

“P.S.—I break open this letter myself, to add my thoughts about some extraordinary things in Mr. Davenport’s conduct. As to his making his judgment about the internal states of persons or their experience, a term of church fellowship, I believe it is unscriptural, and of awful tendency to rend and tear the church. It is bottomed upon a false base,—viz.: that a certain and infallible knowledge of the good estate of men is attainable in this life from their experience. The practice is schismatical, inasmuch as it sets up a term of communion which Christ has not fixed. The late method of setting up separate meetings upon the supposed unregeneracy of pastors is enthusiastical, proud, and schismatical. All that fear God ought to oppose it as a most dangerous engine to bring the churches into the most damnable errors and confusions. The practice is built upon a twofold false hypothesis—infallibility of knowledge, and that unconverted ministers will be used as instruments of no good in the church. The practice of openly exposing ministers who are supposed to be unconverted, in public discourse, by particular application of times and places, serves only to provoke them instead of doing them any good, and declares our own arrogance. It is an unprecedented, divi-sial, and pernicious practice. It is lording it over our brethren to a degree superior to what any prelate has pretended, since the coming of Christ, so far as I know, the pope only excepted; though I really do not remember to have read that the pope went on at this rate. The sending out of unlearned men to teach others upon the supposition of their piety in ordinary cases seems to bring the ministry into contempt, to cherish enthusiasm, and bring all into confusion. Whatever fair face it may have, it is a most perverse practice. The practice of singing in the streets is a piece of weakness and enthusiastical ostentation.

“I wish you success, dear sir, in your journey; my soul is grieved for such enthusiastical fooleries. They portend much mischief to the poor church of God if they be not seasonably checked. May your labours be blessed for that end! I must also express my abhorrence of all pretence to immediate inspiration or following immediate impulses, as an enthusiastical, perilous ignis-fatuus.”

[1] This letter was published in the Pennsylvania Gazette, and can also be found reprinted in Hodge’s History of the Presbyterian Church.

[2] Brainerd to Bellamy, March 26, 1743, writes as follows—“The Moravian tenets cause as much debate as ever; and for my part I’m totally lost and non-plussed about ‘em, so that I endeavour as much as possible to suspend my judgment about ‘em, for I cannot tell whether they are eminent Christians, or whether their conduct is all underhanded policy and an intreague of Satan. The more I talked to Mr. Noble and others, the more I was lost and puzzled; and yet Mr. Nobel must be

a Christian.