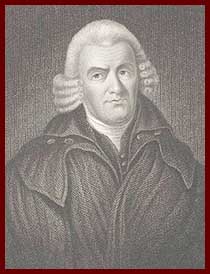

John Brown of Haddington (1722 – 19 June 1787), was a Scottish pastor and author. His works include The Self-Interpreting Bible, The Dictionary of the Bible, and A General History of the Christian Church.

John Brown of Haddington (1722 – 19 June 1787), was a Scottish pastor and author. His works include The Self-Interpreting Bible, The Dictionary of the Bible, and A General History of the Christian Church.

Born at Carpow in the parish of Abernethy, in Perthshire, Scotland, he was the son of a self-educated weaver and river-fisherman, also called John Brown [At which point I have to ask, are the designations of “Jr.” and “Sr.” a more recent innovation?]. His own formal education was scanty, and after both of his parents died when he was about 12, he became a shepherd. It was at about that time that he to know Christ as his Lord and Savior, though details of his conversion are lacking.

Brown taught himself Latin, Greek, and Hebrew just by comparing the English text of Scripture with texts set in those languages. In 1738, after hearing that a Greek New Testament was available in a local bookshop, he left his sheep with a friend and walked 24 miles to St. Andrews to purchase a copy. There he met Dr. Francis Pringle, a professor of Greek who challenged him to read from it, saying that he would buy it for him if he could do so; Brown succeeded. His learning led to controversy among the members of the Secession Church, to which he belonged, as some claimed he had managed his remarkable learning with the aid of the devil.

Over the next few years, Brown worked as a teacher and aided his small income by peddling common kitchen wares. He also had a turn as a soldier, oddly enough, on the side of the Jacobites during the Rebellion of Forty-Five, having volunteered with his best friend, Tim Knab.

At last, and following a division in the Secession Church, the need arose for preachers in the Burgher branch, and Brown was the first new divinity student. He was ordained as a minister at Haddington, East Lothian, on 4 July 1751, and that was his home for the rest of his life. He was called to occupy the position of Moderator of the Synod for the year from November 1753. His first publication was in 1758, and he published regularly from that date until the end of his life.

Brown also, while continuing his duties as a minister, took up the position of professor of divinity by the unanimous agreement of the Synod from 1768. From 1768 until the year of his death he also had the permanent post of clerk of the synod.

His contacts with three famous contemporaries have been documented:

- In 1771 Brown began a long correspondence with Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. which encouraged them mutually in their Christian endeavour.

- In 1772 Brown was walking in Haddington Cemetery when he met Robert Fergusson, the poet, in a dark mood.

- The philosopher David Hume commented that Brown preached “as if he were conscious that Christ was at his elbow”.

Brown died at his home in Haddington on 19 June 1787, after months of stomach problems.

John Brown wrote numerous books, of which the most notable are described here.

Only one dictionary of the Bible (by Thomas Wilson (1563–1622)), by then long out of print, had preceded Brown’s The Dictionary of the Bible. It therefore met a need and after the initial edition published in 1769 numerous editions, variously amended, were issued until 1868. It expressed a Calvinist theology, and in it, the author estimated that 2016 would see the Millennium. Many articles in it are long and appear to be tracts or sermons.[1]

A General History of the Christian Church was issued in two volumes in 1771.

The Self Interpreting Bible was Brown’s most significant work, and it remained in print (edited by others), until well into the twentieth century. The objective of providing a commentary for ordinary people was very successful. The idea that the Bible was “self-interpreting” involved copious marginal references, especially comparing one scriptural statement with another. Brown also provided a substantial introduction to the Bible, and added an explication and “reflections” for each chapter.

A measure of its popularity is that it was translated into Welsh, and its appearance in Robert Burns‘s “Epistle to James Tennant”,

My shins, my lane, I sit here roastin’

Perusing Bunyan, Brown and Boston,

Bibliography[edit]

John Brown’s works[edit]

- 1758, A Help for the Ignorant

- 1765, The Christian Journal

- 1766, An Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of the Secession

- 1767, Letter on the Constitution, Government, and Discipline of the Christian Church

- 1768, Sacred Typology

- 1769, A Dictionary of the Bible

- 1771, A General History of the Christian Church

- 1778, The Self-interpreting Bible

- 1780, The Duty of Raising up Spiritual Children to Christ

- 1782, The Young Christian

- 1783, Practical Piety exemplified in the Lives of Thirteen Eminent Christians

- 1784, A Compendious History of the British Churches

- 1785, Thoughts on the Travelling of the Mail on the Lord’s Day[2]

Family[edit]

Brown had six sons, from two marriages, of whom four became ministers, and another the provost of Haddington. His great-grandson John Brown was known as a physician and essayist

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Mackenzie, Robert (1964) John Brown of Haddington. The Banner of Truth Trust p120

- Jump up^ Brown, John. Brown’s Self-interpreting Family Bible. Green Street Bradford: Edward Slater.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading[edit]

- Robert Mackenzie, John Brown of Haddington 1918 (Paperback 1964 The Banner of Truth Trust)

- J. Brown Patterson, Memoir of the Rev. John Brown