Man Knows Not His Time.

“So teach us to number our days, that we may apply our hearts unto wisdom.”—(Psalm 90:12, KJV)

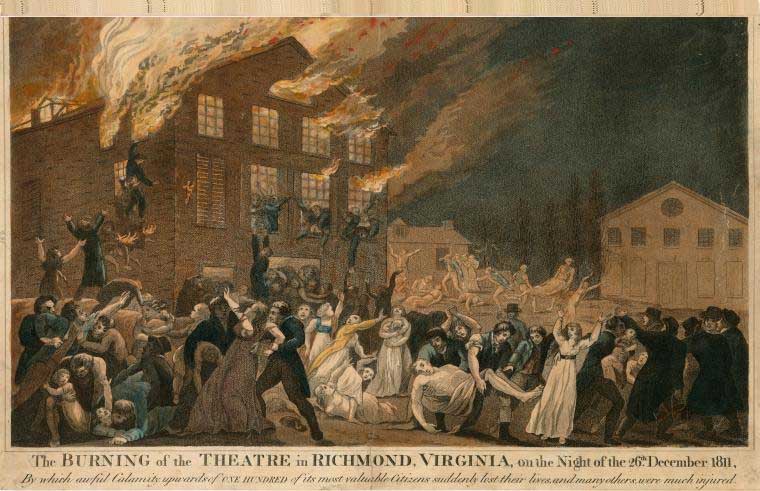

It was on this day, January 19th, in 1812, that the Rev. Dr. Samuel Miller delivered a sermon “at the request of a number of young gentlemen of the city of New-York who had assembled to express their condolence with the inhabitants of Richmond, on the late mournful dispensation of Providence in that city.” A terrible event, the tragedy caught the attention of the young nation, and throughout the Church, not a few pastors addressed themselves to various aspects of the horrible fire. [See a partial list at the end of the sermon text, below.] By way of background, as Dr. Miller himself relates in a note suffixed to his sermon:—

“On the night of December 26, 1811, the theatre in the city of Richmond, Virginia, was unusually crowded; a new play having drawn together an audience of not less than six hundred persons. Toward the close of the performances, just before the commencement of the last act of the concluding pantomime, the scenery caught fire, from a lamp inadvertently raised to an improper position, and, in a few minutes the whole building was wrapped in flames. The doors being very few, and the avenues leading to them extremely narrow, the scene which ensued was truly a scene of horror! It may be in some degree imagined, but can never be adequately described!—About seventy-five persons perished in the flames. Among these were the governor of the State; the President of the Bank of Virginia; one of the most eminent Attorneys belonging to the bar of the commonwealth; a number of other respectable Gentlemen; and about fifty females, a large portion of whom were among the Ladies of the greatest conspicuity and fashion in the city.”

In Dr. Miller’s sermon, the first two major points of his sermon are much more in keeping with what we might expect. However, in his third division of the sermon—the moral application—Miller uses the occasion to speak out against the theatre as an institution. In this, he echoed a common sentiment among Christians of his day, who generally opposed the theatre and the profession of acting.

For those with the time and interest to read, the text of Dr. Miller’s sermon follows.

A SERMON.

Lamentations 2:1,13: How hath the Lord covered the daughter of Zion with a cloud in his anger, and cast down from heaven unto the earth, the beauty of Israel, and remembered not his footstool in the day of his anger! What thing shall I take to witness for thee? What thing shall I liken to thee, O daughter of Jerusalem? What shall I equal to thee, that I may comfort thee, O virgin daughter of Zion? For thy breach is great like the sea; who can heal thee?

THE prophet Jeremiah lived in a dark and distressing day. Religion, among his countrymen, had sunk to an ebb awfully low. The body of the people had become extremely licentious in principle, and corrupt in practice. And a holy God had visited them with many tokens of his righteous displeasure. By fire, by famine, by pestilence, and by the sword, he had taught them terrible things in righteousness; until, at length, wearied with their iniquities, he delivered them into the hands of their enemies, by whom they were, as a people, nearly destroyed.

Over this melancholy scene of guilt and suffering the Prophet composed his Lamentations. And never were scenes of misery, and feelings of anguish, painted with a more masterly hand. Never were the pathos and tenderness, as well as the force of grief, more strongly displayed. As one of the ancient Fathers beautifully expresses it, “every letter appears to be written with a tear, and every word to be the sound of a broken heart; and the writer a man of sorrows, who scarcely ever breathed but in sighs, or spoke but in groans.”

Having been requested, on this occasion, to address my audience with reference to a late awful calamity, well known to you all, which had destroyed many valuable lives, and has covered a sister City with mourning; I have chosen the words just read as the foundation of what shall be offered. May the great Master of assemblies direct us to such an application of them as shall be profitable to every hearer!

How hath the Lord covered the daughter of Zion with a cloud in his anger, and cast down from heaven unto earth, the beauty of Israel! What shall I take to witness for thee? What thing shall I liken unto thee, O daughter of Jerusalem? What shall I equal to thee, that I may comfort thee, O daughter of Zion? For thy breach is great, like the sea; who can heal thee?

Without staying, at present, to explain in detail the several parts of this passage, I shall only observe, that by the daughter of Zion, and the daughter of Jerusalem, we are to understand, by a figure common with this Prophet, the inhabitants of the Jewish capital, in which Zion stood; or rather the Jewish nation, the covenanted people, the visible Church of God, under the Old Testament economy. Of course, what the Prophet applies to that afflicted city, may, without impropriety, be applied either to the whole, or any part of a community, who call themselves a Christian people; or who are embraced even by the most lax profession, within the pale of the visible Church.

We may therefore consider the text first, as a devout acknowledgment of the hand of God, in the afflictions which the Prophet laments;—secondly, as an expression of sympathy with the afflicted;—thirdly, as pointing to the moral application of the calamities which he deplored.

I. There is, in the passage before us, a devout acknowledgment of the hand of God, in the affliction which the prophet laments. How hath the LORD covered the daughter of Zion with a cloud in his anger! How hath the LORD cast down the beauty of Israel!

The doctrine, that the providence of God extends to all events, both in the natural and moral world; that nothing comes to pass without either his direct agency, or, at least, his wise permission and control; is a doctrine not only laid down in the plainest and most pointed manner in scripture; but also one which results from the perfections and the government of God when admitted in almost any sense. If there be a general providence, there must be a particular one. If God govern the world at all, he must order and direct everything, without exception. Yes, brethren, if it were possible for a sparrow to fall to the ground without our heavenly Father; or if it were possible for the hairs of any head to fail of being numbered by the infinite One; in short, if it were possible that there should be anything not under the immediate and the constant control of the Governor of the world; then it would follow that some things may take place contrary to his will; then prayer would be a useless, nay, an unmeaning service; then Jehovah would be liable, every moment, to be arrested or disappointed in the progress of his plans, by the caprice of accident. But, if none of these things can be supposed without blasphemy, then the providence of God is particular as well as universal. It extends to all creatures, and all their actions.—Is there evil in the city and the Lord hath not done it? No; the devouring fire; the overwhelming tempest; the resistless lightning; the raging pestilence; the wasting famine; and the bloody sword, even when wielded by the vilest of men, are all instruments in the hand of God for accomplishing his will and pleasure. And as the providence of God is actually concerned in every thing which befalls individuals or communities; so he requires us to notice and to acknowledge that providence in all his dispensations towards us. Not to regard the work of the Lord, or not to consider the operation of his hands, he pronounces to be sin; and denying his agency in the works of providence, he expressly condemns, as giving his glory to another.

While, therefore, we deplore the heart-rending calamity which had fallen upon a neighboring city, let us not forget, or place out of sight, the hand of God in the awful scene. It was not the work of chance. A righteous God has done it. His breath kindled the devouring flame. Not a spark of the raging element rose or fell without his providential guidance: not a victim sunk under its destroying power, without the discriminating and immediate hand of sovereign Wisdom. He ordered and controlled all the circumstances attending the melancholy scene. He doth not, indeed afflict willingly, nor grieve the children of men. But still affliction cometh not forth of the dust, neither doth trouble spring out of the ground. What! shall we receive good at the hand of God, and shall we not receive evil also? The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord!

II. The Language of the mourning Prophet, while it notices and acknowledges the hand of God in the calamities which it deplores, at the same time expresses the tenderest sympathy for the sufferers. This is indicated in every line of our text and context: and it is the feeling which ought to be cherished upon every similar occasion.

To sympathize with suffering humanity, however that suffering may have been produced, is a dictate of nature, as well as demanded by the authority of our common Creator. Thou shalt weep with them that weep, is a divine precept. When one member of the body suffers, all the members suffer with it. Thus it is in the social as well as in the physical body. Thus it is in domestic society. And thus it ought to be in the large family of a city, a state, or a nation. When one part of a nation is afflicted, all the rest ought to feel for it. When, therefore, any of our friends or neighbors, or any of the most remote portions of the same associated family are visited with any signal calamity, we are bound to consider it not only as a solemn lesson addressed to the whole body; but also as calling upon us to feel for, and sympathize with them; as they, under like circumstances, ought to sympathize with, and feel for us. When this is not the case, one great design of Jehovah’s judgments, which is to instruct and to impress a whole people, by the calamities of a part, is, undoubtedly, speaking after the manner of men, opposed and defeated.

The melancholy dispensation of providence which we this day deplore, is one pre-eminently calculated to interest the feelings, and to excite the tenderest sympathy of very mind. How shall we speak of a scene of such complicated horror? The heart sickens at the dreadful recital! When our beloved relatives die on the bed of disease, the event is solemn, and the bereavement trying; but it is the course of nature; and the frequency of the occurrence disarms it of more than half its terrors. When our friends and neighbors fall in battle, the stroke is painful; but the soldier is expected, by himself and by others, to be in danger of such an end. When those who sail on the mighty deep, are dashed on the rocks, or swallowed up in the merciless waves, we mourn over the catastrophe; but when be bade them farewell, we remembered that they might never return.

But how shall we describe a calamity which has plunged a whole city into agony and tears? A calamity which, to the number and the importance of its victims, added all the circumstances of horror which can well be conceived, to overwhelm the mind! How sudden the burst of destruction! How unexpected its approach, at such a place, and at such a time! What complicated agony, both to the sufferers and to the survivors, attended its fatal progress! But I dare not attempt further to depict a scene from which the mind revolts with shuddering!

Is there a Husband or a Wife who does not feel for those who saw beloved companions writhing in the merciless flames, and sinking in the most dreadful of all deaths, without being able to afford them relief? Is there a Parent who does not feel for those agonizing fathers and mothers, who saw their endeared and promising children torn from them in an hour of unsuspecting confidence and mirth? Is there a Brother or a Sister who does not sympathize with those almost frantic survivors, who were compelled to abandon to their cruel fate relatives dear to them as life? Is there a Patriot who does not feel for the fatal stroke which snatched an amiable and respectable Chief Magistrate from the bosom of a beloved family, and from the confidence of his fellow citizens? Is there a mind capable of admiring the attractive, the interesting, and the elegant, who is not ready to drop a tear over youth, beauty, genius, learning, and active worth, all sinking together in one smoking ruin? Is there a heart alive to the delights of society, and the endearments of friendship, who does not mourn over the melancholy chasm, which has been made in the social circles of that hapless city?—O Richmond! bereaved and mourning Richmond! What shall we say unto thee? How shall we comfort thee? Thy breach is great like the sea; who can heal thee? None but that God who has inflicted the stroke! O that our heads were waters, and our eyes fountains of tears, that we might weep over the slain of the daughter of thy people!

III. We may consider the passage before us as pointing to the moral application of the calamities which it deplores. Read the rest of this entry »

![Rev. Samuel Davies [3 November 1723 - 4 February 1761]](https://thisday.pcahistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/DaviesSamuel-231x300.jpg)