October 6: Rev. Robert Baird [1798-1863]

October 6: Rev. Robert Baird

July 14: The Certainty of the World’s Conversion

As is our habit this year on TDPH, on each Lord’s Day we look to post a sermon (or a reasonable facsimile thereof). Also, since it is Sunday, hopefully our readers will have more time to read these longer entries, and we trust you will find them profitable. The text of today’s post is permanently posted in PDF format at the PCA Historical Center’s web site, here.

THE CERTAINTY OF THE WORLD’S CONVERSION.

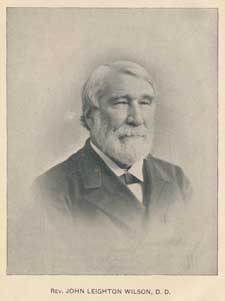

BY REV. J. L. WILSON,

Missionary at the Gaboon, W. Africa.

[excerpted from The Southern Presbyterian Review, vol. 2, no. 3 (December 1848): 427-441.]

“It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.” This stern declaration wrung from the disciples of Christ the earnest inquiry, “Who then can be saved?” To this the Saviour replies, “With men this is impossible, but with God all things are possible.”

“It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.” This stern declaration wrung from the disciples of Christ the earnest inquiry, “Who then can be saved?” To this the Saviour replies, “With men this is impossible, but with God all things are possible.”

In this reply, there is no abatement of the real difficulties of being saved. The impressions of the disciples, on this particular point, were correct, and no effort is made to change or remove them. The kingdom of heaven, if taken at all, must be taken by violence, and none but the violent shall ever enter. It has a straight gate and a narrow way; and it is only those who enter the one and walk in the other that shall ever attain to everlasting life. The immutable terms of discipleship are, that we must take up our crosses and follow Christ, through evil as well as good report. Those who shine in the upper courts with most lustre, are those who have come out of great tribulation and made their garments white in the blood of the Lamb.

The impressions of the disciples, therefore, are rather confirmed than removed. According to their previous views, and those of the young man with whom the Saviour had just been conversing, it was not possible to be saved. Both were indulging fundamental errors on the most important of all subjects, and it was essential to their salvation that those errors should be corrected.

But whilst the foundation upon which they were standing is thus torn away, they are not given over to despair. A surer and better way is pointed out. That which they could never attain by their own exertions or morality, can easily be effected by the grace of God. In other words, what is impossible with men is possible with God. What we can never effect by our own unaided efforts, may easily be achieved by throwing ourselves upon the almighty power of Jehovah.

This doctrine accords with the experience of Christians in all ages of the world. There is no lesson more thoroughly taught in the school of Christ than this. Christians who have had even but little experience, are fully aware that they can make no advances in holiness, except so far as they are aided from on high. A clear view of the number and power of their spiritual enemies, if not attended by equally clear views of the all sufficiency of divine grace, never fails to awaken apprehensions about their final salvation; whilst a lively appreciation of the promises and assurances of the Bible, and right apprehensions of the power of God, as seldom fail to inspire them with courage and resolution.

Nor is this principle of dependence upon God, more important or indispensable in our personal conflicts with sin, than it is in every enterprise in which we engage for the benefit of others. “Without me,” says the Saviour, “ye can do nothing.” But then again it is said with equal emphasis, “I can do all things through Christ, which strengtheneth me.”

Guided by this principle of dependence, there is no enterprise, however great or difficult, provided it is in accordance with the Divine will, upon which we may not enter with confident assurance of success. It matters not what human probabilities may be arrayed against it,—it matters not what disproportion there may be between the means and the end to be effected,—it matters equally little whether we are able or not to trace all the intermediate steps by which it is to be brought about,—nor are we to be discouraged or intimidated because unforeseen difficulties rise and threaten to frustrate our work. It is enough for us to know that we are engaged in a cause that has been authorised by God, and that we pursue it in a manner that he approves. Having settled these fundamental principles, we may press forward in any good work, with confidence that our labour shall not be in vain in the Lord.

These general remarks have been made for the purpose of introducing our general subject, the certainty of the world’s conversion.

There are multitudes in the Christian church, at the present moment, who are pressed with difficulties in relation to this matter, not unlike those which the disciples once felt in relation to the salvation of their own soul. And who is there among us, Christian hearers, who does not in some measure, at least, participate in feeling these difficulties.

No doubts are entertained in relation to what the Bible teaches on this subject. The mass of Christians believe, or profess to believe, that “all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of God.” But the overwhelming magnitude of the work fills the mind with doubts and skepticism, and leads many to abandon the missionary cause, as a visionary and hopeless work.